Exploratory Testing

18 November 2019

Exploratory testing is a style of testing that emphasizes a rapid cycle of learning, test design, and test execution. Rather than trying to verify that the software conforms to a pre-written test script, exploratory testing explores the characteristics of the software, raising discoveries that will then be classified as reasonable behavior or failures.

The exploratory testing mindset is a contrast to that of scripted testing. In scripted testing, test designers create a script of tests, where each manipulation of the software is written down, together with the expected behavior of the software. These scripts are executed separately, usually many times, and usually by different actors than those who wrote them. If any test demonstrates behavior that doesn't match the expected behavior designed by the test, then we consider this a failure.

For a long time scripted tests were usually executed by testers, and you'd see lots of relatively junior folks in cubicles clicking through screens following the script and checking the result. In large part due to the influence of communities like Extreme Programming, there's been a shift to automating scripted testing. This allows the tests to be executed faster, and eliminates the human error involved in evaluating the expected behavior. I've long been a firm advocate of automated testing like this, and have seen great success with its use drastically reducing bugs.

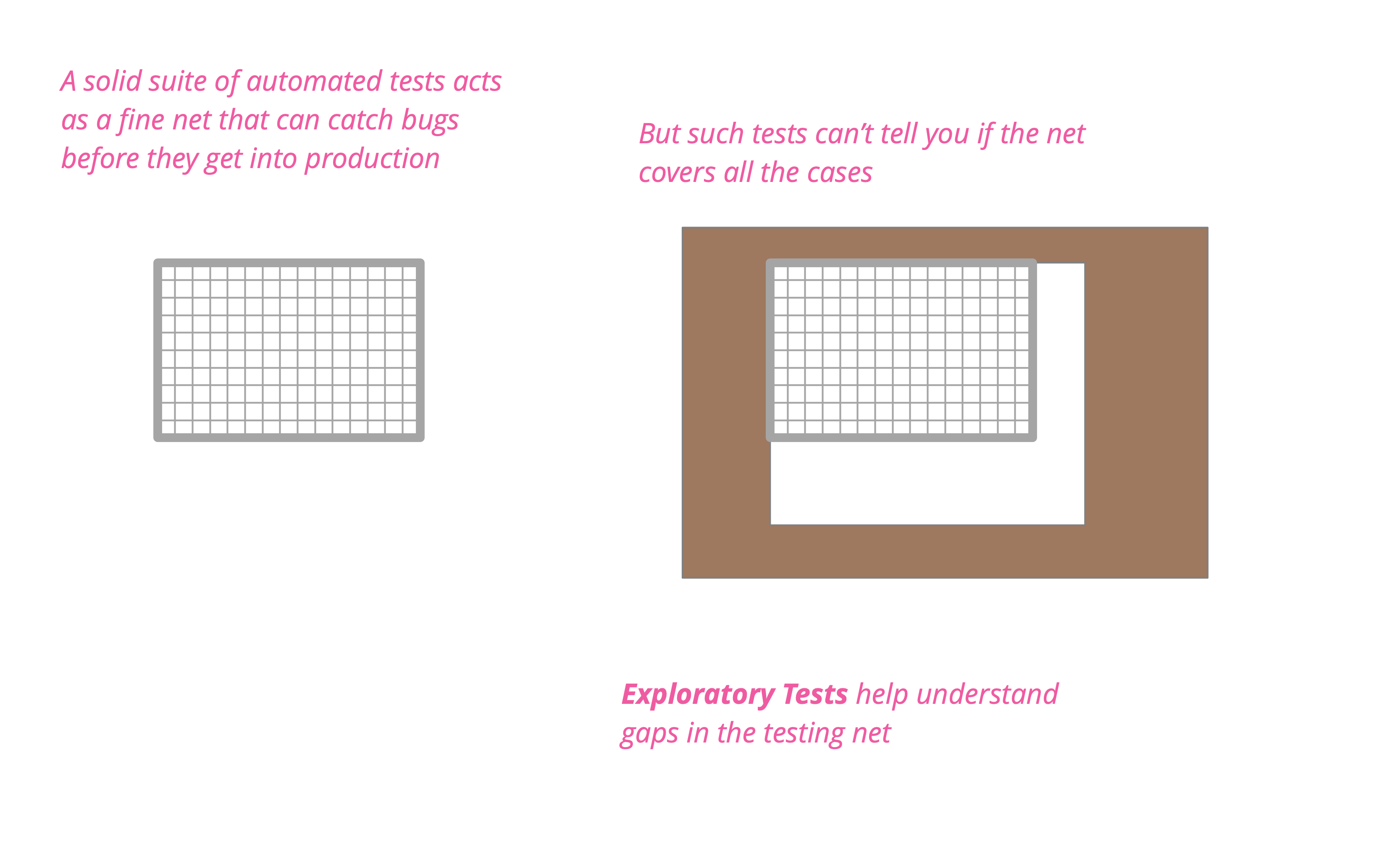

But even the most determined automated testers realize that there are fundamental limitations with the technique, which are limitations of any form of scripted testing. Scripted testing can only verify what is in the script, catching only conditions that are known about. Such tests can be a fine net that catches any bugs that try to get through it, but how do we know that the net covers all it ought to?

Exploratory testing seeks to test the boundaries of the net, finding new behaviors that aren't in any of the scripts. Often it will find new failures that can be added to the scripts, sometimes it exposes behaviors that are benign, even welcome, but not thought of before.

Exploratory testing is a much more fluid and informal process than scripted testing, but it still requires discipline to be done well. A good way to do this is to carry out exploratory testing in time-boxed sessions. These sessions focus on a particular aspect of the software. A charter that identifies the target of the session and what information you hope to find is a fine mechanism to provide this focus.

Such a charter can act as focus, but shouldn't attempt to define details of what will happen in the session. Exploratory testing involves trying things, learning more about what the software does, applying that learning to generate questions and hypotheses, and generating new tests in the moment to gather more information. Often this will spur questions outside the bounds of the charter, that can be explored in later sessions.

Exploratory testing requires skilled and curious testers, who are comfortable with learning about the software and coming up with new test designs during a session. They also need to be observant, on the lookout for any behavior that might seem odd, and worth further investigation. Often, however, they don't have to be full-time testers. Some teams like to have the whole team carry out exploratory testing, perhaps in pairs or in a single mob.

Exploratory testing should be a regular activity occurring throughout the software development process. Sadly it's hard to find any guidelines on how much should be done within a project. I'd suggest starting with a one hour session every couple of weeks and see what kinds of information the sessions unearth. Some teams like to arrange half-an-hour or so of exploratory testing whenever they complete a story.

If you find bugs are getting through to production, that's a sign that there are gaps in the testing regimen. It's worth looking at any bug that escapes to production and thinking about what measures could be taken to either prevent the bug from getting there, or detecting it rapidly when in production. This analysis will help you decide whether you need more exploratory testing. Bear in mind that it will take time to build up the skill to do exploratory testing well, if you haven't done much exploratory testing before.

I would consider it a red flag if a team isn't doing exploratory testing at all - even if their automated testing was excellent. Even the best automated testing is inherently scripted testing - and that alone is not good enough.

Acknowledgements

Almost all I know about Exploratory Testing comes from Elisabeth Hendrickson's fine book, which is also where I pinched the net metaphor from.

Aida Manna, Alex Fraser, Bharath Kumar Hemachandran, Chris Ford, Claire Sudbery, Daniel Mondria, David Corrales, David Cullen, David Salazar Villegas, Lina Zubyte, and Philip Peter discussed drafts of this article on our internal mailing list.