This pattern is part of “Patterns of Legacy Displacement”

Feature Parity

Replicate existing functionality of a legacy system using a new technology stack.

27 July 2021

On many occasions when we find ourselves talking to IT executives we hear how they have a suite of aging applications built using soon to be, if not already end of life technologies. More often that not these systems are hosted in costly data centers managed by 3rd parties and with inflexible contracts. These applications are critical to the successful operation of the business, while at the same time being one of the largest sources of business and operational risk.

They are all too aware that there is an chance to make improvements, optimize processes and unlock new opportunities. To do this fully however is going to be disruptive and brings in many dependencies. For instance the commitments of existing 'BAU' work, other change programmes and not least the existing plans and budgets of the departments where the end users work.

One approach in this situation is to try to minimize the impact of replacement on the broader organization by 'simply' replacing the technology while leaving everything else 'as is'. This is approach often referred to as Feature Parity, or the 'feature parity trap' by those who have tried it.

Whilst Feature Parity often sounds like a reasonable proposition, we have learnt the hard way that people greatly underestimate the effort required, and thus misjudge the choice between this and the other alternatives. For example even just defining the 'as is' scope can be a huge effort, especially for legacy systems that have become core to the business.

Most legacy systems have 'bloated' over time, with many features unused by users (50% according to a 2014 Standish Group report) as new features have been added without the old ones being removed. Workarounds for past bugs and limitations have become 'must have' requirements for current business processes, with the way users work defined as much by the limitations of legacy as anything else. Rebuilding these features is not only waste it also represents a missed opportunity to build what is actually needed today. These systems were often defined 10 or 20 years ago within the constraints of previous generations of technology, it very rarely makes sense to replicate them 'as is'.

If Feature Parity is a genuine requirement then this pattern describes what it might take to do well. It is not an easy path, nor one to be taken lightly.

How It Works

Feature parity is simple concept to state. Build a new system, in a more appropriate technology stack, with exactly the same features and behaviors as the existing system. Whenever anyone has a question about what the new system should do, we answer that question with “do what the existing system does”. To know we have parity we need to fully understand what the current system does, and be able to verify the new system does that same thing.

What is in scope - what does the old system do?

The first part of feature parity is to create a specification of what the current system does. A combination of the following will likely be required:

System Surveys

User Actions

What are the user roles, what features (menu items) in the system can they see, what actions can they perform. For each menu item / action - what are the screens involved, what data items, what validation logic can you see. What observable result is there for a user taking the action?

Batch processes

What batch jobs are defined in the system? When are they triggered, what processing do they perform, what observable results are there?

Interfaces and Integrations

What systems are integrated?

- What interfaces does this system provide to its customers, what are the contracts (API, CFRs, behaviour expectations/side effects)

- What interfaces does this system consume, what are those contracts?

- Look out for systems or parts of systems that are integrated via databases (see Reports / Data, and Archeology)

Core algorithms

Well known business rules and calculations that need to be replicated - triggered by user actions, batch processes.

Reports / Data

What reports does the system create, in what format, from what data, when and how frequently?

How is the data mutated within the database? Are there triggers altering the data, what fires them, and what procedures do they fire? How deep does that rabbit hole go?

What other systems have access to or are integrated using this data? In what ways do they change it, and what observable behaviour do those changes have?

Archeology

Archeology is often needed to fully understand what a system does. It is through an “archaeological process” that you learn that changing the data field Y on screen A results in value Z appearing on report C after batch job N runs. Performing this archeology can be a significant investment in time, and brain power of those people with the most experience of your legacy systems.

Instrumentation - based on data, what is used?

It is well worth spending some time analysing existing reports such as access or other system logs to understand how the current system is used. If these are not available, then some investment in instrumenting the existing system may provide a good return as it could allow you to avoid unnecessary work based on data.

Feature value - can we drop features that are low value?

Whilst we are trying to avoid burdening the business when adopting this pattern, talking to users to understand what features are low value or not used can be helpful to manage your scope. This will re-introduce the organisational impacts/change that we were trying to avoid though.

Use tests to ensure feature parity - the new system does what the old one did

Knowing what the old system does is the first challenge, but we also need to be sure that the new system does indeed work the same way. To verify this with confidence we need tests in place to prove that the new system does indeed have feature parity. Following is a list of areas where testing will need to be implemented.

User journeys and user experience

Use acceptance tests - to check that features you have built behave as expected from a user's perspective. Take care not to be reliant on these as the main validation approach as they are high up the testing pyramid. Additionally be mindful that decomposing a system into user functions, screens and flows could easily lead to too many of these types of tests.

Testing UI behaviour (including client side validation) is relatively simple to do: click here, expect to see some state, enter data there, click there, expect to see some different state. Use the appropriate tooling for your chosen tech - unit-like test frameworks for SPA application, or something like Cypress for a more traditional server side rendered application.

Where it is important (in an “expert user optimised” UI for example) the testing of layout (and look/feel) is harder but there are tools that can help (Galen with Selenium for example).

For the usability and layout you will likely be reliant on exploratory testing.

Business logic - core algorithms

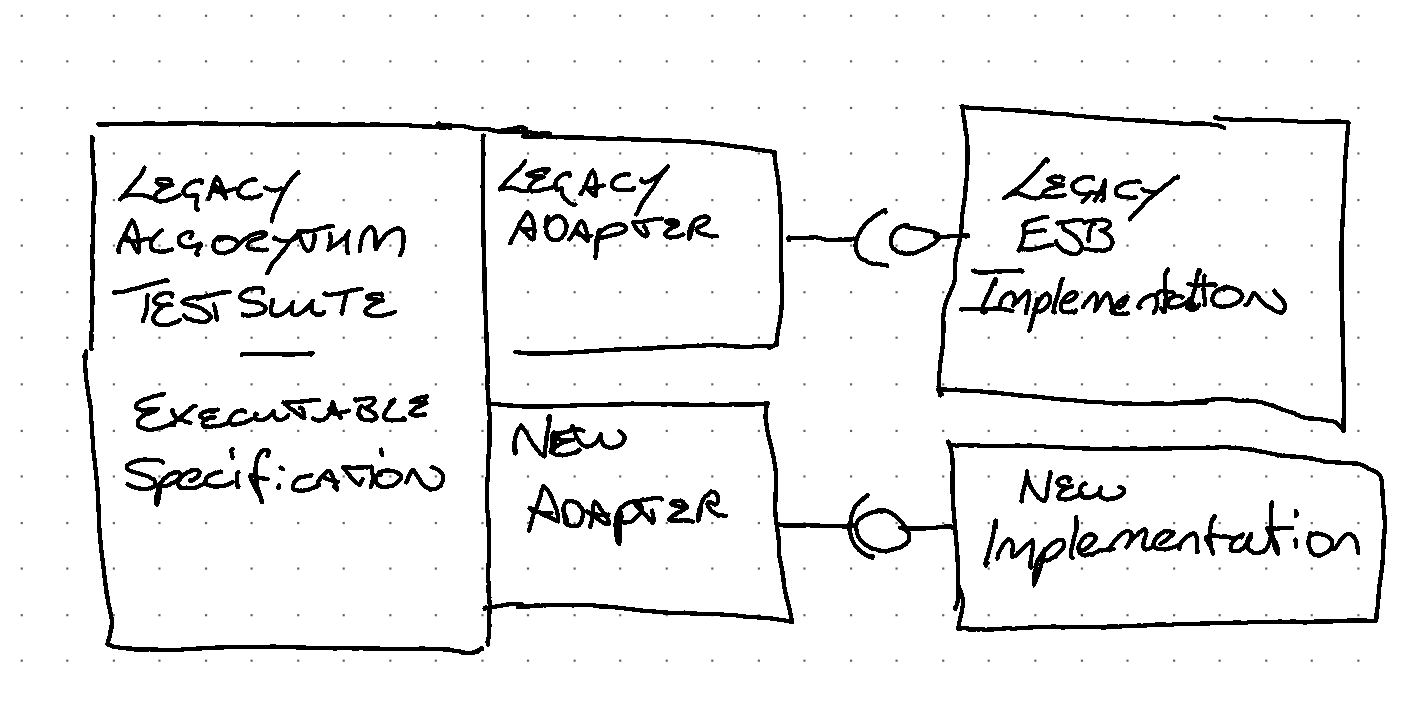

For core algorithms and core business logic, ensure that you have built a suite of unit tests around these parts of the existing system. These will provide executable specifications of the business logic / algorithm that is known to successfully run on the existing system. A modified TDD approach that includes porting these tests into the new tech stack can then be used giving high confidence in the new implementation. There is a risk associated with knowing that you ported the tests correctly - mutation testing could provide some additional reassurances - similar mutations cause similar failures across the old and new implementations.

Interfaces - as a service provider and as a service customer

As service provider: Create a test suite to execute against the existing system being replaced - an executable contract. Execute these same tests against the new replacement system checking for adherence to the contract. Beware the trap of the scope of these tests becoming too large, like in the case of the UI.

As customer: Use test mocks to validate that you are interacting with the provided services in the expected way. Like the case for core business logic, migrate these mocks to the new tech stack to ensure the new implementation continues to interact with provided system in the same way. Additionally use stubs of the external systems to provide known data sets for your new tests.

In both cases: Proxies can be a useful tool to use to ensure feature/interaction parity. By injecting a proxy into the communication path the interactions with the old system can be recorded. You can use these recordings to:

- Replay messages from customers - and check the new system's response

- Create stubs that can replay known good responses

Databases and reports: This can be really hard - like UI tests beware the top of the pyramid. Here the database / reports are another type of interface. Successfully testing them will require lots of test data - typically hard to create/manage.

Implementation and tracking progress

With a completed system survey to define scope, and a comprehensive suite of tests in place to provide an executable specification of behaviour your implementation can proceed with relative confidence. But how to track progress?

By Menu Item / User Action

(or other parts identified when surveying system) This can be dangerous, as there is a risk that the things you are tracking may be sliced by layer (or architectural concern) Slicing by architectural layer severely impacts the delivery of value, and reduces visibility of progress. (i.e. no value is unlocked and no _real_ progress is made until a feature is delivered top to bottom).

A key assumption here is that the Item or Action can deliver Value for end users on it's own. Unfortunately this is often not the case, we might deliver 80% of individual process steps but still be unable to complete the whole business process within the new system. This is an unfortunately common situation, with high levels of completeness being reported and yet an inability to test or release usable software.

Vertical slices

Provide better transparency of progress, but it is likely that vertical slices will not be the output of the system surveys. So mapping has to be done - more work, and a risk that requirements fall through the gaps.

End to end processes

Track progress based on the full of migration of individual business processes into the new solution, so the test becomes: can a process be fully completed wholly within the replacement system. This can be combined with tracking by User Actions, above, but only if we ensure the work done to deliver individual process steps is prioritised by the “owning” business process.

The authors' preference would be to ensure that the definition of done for any piece of work includes (where possible) the complete end-to-end scope across all layers.

When to Use It

We have presented above our view on what is required in order to apply this pattern well, and increase your chances of success. If feature parity is the aim, then there is significant work involved in determining what is required in terms of features, and more work associated with ensuring that the feature parity goal has been met through testing.

In general this is a pattern that we don't recommend. In fact Thoughtworks went as far as placing this very pattern on hold in our Technology Radar. We see this pattern as a huge missed opportunity. Often the old systems have bloated over time, with many features unused by users (50% according to a 2014 Standish Group report) and business processes that have evolved over time. Replacing these features is a waste. Instead, try to muster the energy to take a step back and understand what users currently need, and prioritize these needs against business outcomes and metrics.

We have however seen a couple of cases where this pattern is particularly applicable.

- Highly optimised user interfaces for power users are good candidates for recreating like-for-like. Consider agents using short-cut keys to execute trades at high speeds. To be effective at their job they may require hyper-optimised user interfaces that enable them to operate using only the keyboard. It may take a significant amount of time to become proficient, and changes that result in lower effectiveness cannot be tolerated.

- Behaviour based on well known specifications: Another example use case for applying the pattern could be systems that support engineering or scientific modelling. In the case of a finite element analysis solver for example, a given input should produce a given output - the laws of physics are not changing as part of the modernization project.

One could argue that in both of these cases the need for feature parity is somewhat localised - by which I mean constrained to a particular part of the system. It is questionable that the approach to managing scope of the modernization of the whole system be constrained by these localised use cases.

But these cases, while valid, are still exceptional. Overwhelmingly we've seen feature-parity exercises be a tale of frustration. The cost and effort required to properly understand existing features mushrooms, leading to corners being cut, and although some of these are unused features that ought to be cut, usually some vital features also feel the knife. If all goes well, the business pays a handsome sum of money for no improvement in support for the business. This is not a good story when enterprises know that their future depends on better technology engagement.

Alternative approaches

- Extract Product Lines or Extract Value Streams are both patterns that give strategies for identifying thin slices through an existing system. One of the key differences is that they both offer ways to shorten the feedback cycle while allowing elements of legacy to be disabled and turned off much sooner.

- Looking at the business value and making sure that is represented in any architectural decisions can often highlight issues with Feature Parity driven approaches.

- More “holistic” approaches can help highlight issues with Feature Parity by treating technology and business process as part of the same problem. Specifically in the case of Feature Parity this can often highlight that current business processes are a consequence of the workarounds and compromises required by the legacy technology. Just replacing the tech will leave at least half the problem unsolved.

- User research can help highlight that existing business processes are no longer fit for purpose. In one case by just having a few days of shadowing of existing staff it became clear feature parity was unsuitable as current processes were very broken, it's always a good thing to talk to the end users.

Example: replacement of logistics systems

A logistics organisation was engaged with a plan to replace aging software used for the acceptance, route planning and delivery of packages. As part of this they agreed an IT led initiative with relatively low engagement with the business stakeholders. The technology view was that they could just do “feature parity” thus solving their pressing need to replace out of date tech. As part of this programme a major piece of work was done to replace the system that accepted the packages from clients. We become involved towards the end of this part of the programme.

We felt the low engagement with the business stakeholders presented a risk to the programme, especially as we were hearing via a different project that the business were feel frustrated with the development efforts. As part of this we spoke to the key stakeholders including the finance team. This is when we became aware of a review that had been done that indicated only a relatively small percentage of customers were profitable for the organisation. In turn this meant only a small subset of 'package types' were profitable, many lost the organisation money due to special handling requirements. So the business had a plan in place to stop handling those packages.

It turned out that a very large amount of effort in the “feature parity” project had been spent to deal with exactly those packages, the very ones the business said they no longer needed. The business had hoped that the processes and hence software would be much simpler without these difficult edge cases. In this case “feature parity” led to a large amount of time and money being spent handling requirements the business no longer had, while further damaging the reputation of IT in the eyes of the business.

Example: e-commerce organisation re-platform

This organisation had enjoyed a period of rapid growth but had not prioritized IT spend for several years, this created a relatively urgent need to replace many elements of the current solution. For example during certain periods they had to slow down the number of sales to avoid overwhelming core systems, hardly ideal from a business point of view.

Many of the key business operations were handled by the same mainframe, which had been initially commissioned during the very earliest days of their e-commerce operations. Extracting elements from this system was clearly going to be technically challenging. At the same time business leaders having seen several disruptive failed projects wanted to minimize any further disruption to their staff. A further challenge was current processes and systems made it extremely difficult to prioritize product lines to migrate if a more incremental approach was used. In short it was very difficult to understand which things they sold made money and which things didn't so it was felt the only option was to move everything all at once. Based on these challenges it was felt just replicating what they had was the best and lowest risk approach.

Given current business processes were, on the face of it, all implemented together in the same mainframe this meant the scope of any “feature parity” replacement was in essence all the main activities and processes of the entire business. They embarked on an effort to document the “in scope” as-is processes for the replacement system, with the plan that this was going to be used as input for a vendor selection process.

Several things soon became clear. One was that it really was going to have to be almost every single activity that the business did, each effort to document “as-is” functionality uncovered more things that would need to included to give “feature parity”. Secondly due to historical workarounds, years of shifting requirements alongside many outstanding bugs the last thing the actual people who worked with the legacy system wanted was the same thing. It almost always made their jobs harder and was a key source of error and delay. Finally due to the bugs and workarounds it became clear several key processes were in fact being run “off system” on hand-built spreadsheets. Key business data was extracted from the mainframe, used to run a business process via the spreadsheet, then later on the now modified data was uploaded to back the mainframe.

At this point it was felt by some that “feature parity” was becoming too risky, with scope continually growing. This was before the requirements gathering process was complete, and there was no clear end date for that effort. Our involvement ceased at this stage as we felt continuing with “feature parity” was too risky and would not deliver what the business needed, not least since lack of key business metrics made prioritisation of any more incremental approach impossible. Several years later they were still doing the “as is” requirements process, way past the original deadlines.

Lack of the right metrics and ability to prioritize elements of functionality from a business point of view can often force organisations into a “feature parity” approach. In this case we think it likely a initial effort to gather key business metrics around various product lines could have suggested ways to break the problem up. It's a great illustration that you can't make the right technical decisions without the right business context and involvement.

Example: a successful replacement of a financial calculation service

One of our teams was working for a large financial organisation. They wanted to modernise an existing service that performed complex financial calculations. The specification of the financial calculations was fixed, the interface to the service was similar only the technology needed to be updated - from a J2EE Session EJB implementation, to a SOAP Web Service in the latest (at that time) version of Java.

The team created a rich test suite around the existing implementation with clean separation between set-up, execution and assertion responsibilities.

Figure 1: tests_for_feature_parity

Once the tests were in place, the execution adapter could be replaced with minimal risk, and a new implementation created meeting the same executable specification as the old system.

This page is part of:

Patterns of Legacy Displacement

Patterns

Significant Revisions

27 July 2021: