Assessing internal quality while coding with an agent

This article is part of “Exploring Gen AI”. A series capturing Thoughtworks technologists' explorations of using gen ai technology for software development.

27 January 2026

There’s no shortage of reports on how AI coding assistants, agents, and fleets of agents have written vast amounts of code in a short time, code that reportedly implements the features desired. It’s rare that people talk about non-functional requirements like performance or security in that context, maybe because that’s not a concern in many of the use cases the authors have. And it’s even rarer that people assess the quality of the code generated by the agent. I’d argue, though, that internal quality is crucial for development to continue at a sustainable pace over years, rather than collapse under its own weight.

So, let’s take a closer look at how the AI tooling performs when it comes to internal code quality. We’ll add a feature to an existing application with the help of an agent and look at what’s happening along the way. Of course, this makes it “just” an anecdote. This memo is by no means a study. At the same time, much of what we’ll see falls into patterns and can be extrapolated, at least in my experience.

The feature we’re implementing

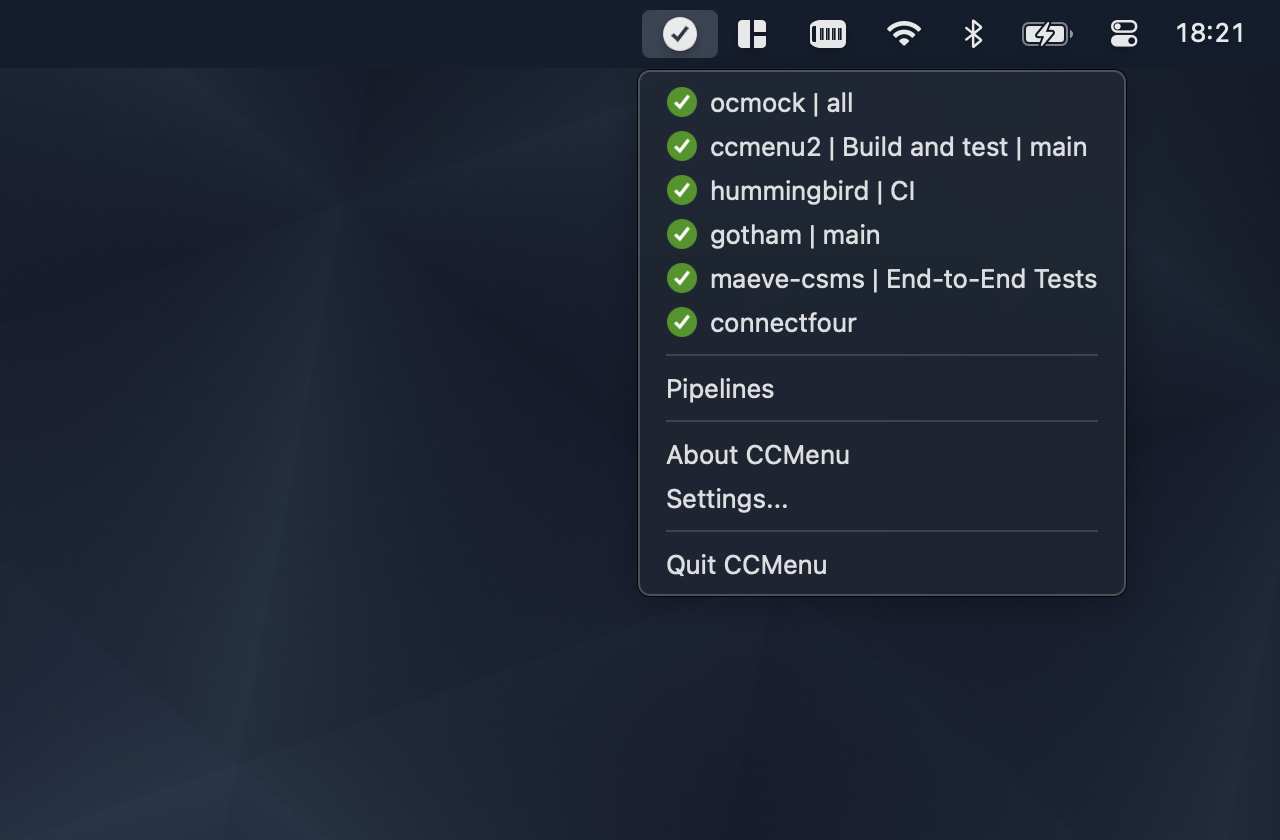

We’ll be working with the codebase for CCMenu, a Mac application that shows the status of CI/CD builds in the Mac menu bar. This adds a degree of difficulty to the task because Mac applications are written in Swift, which is a common language, but not quite as common as JavaScript or Python. It’s also a modern programming language with a complex syntax and type system that requires more precision than, again, JavaScript or Python.

CCMenu periodically retrieves the status from the build servers with calls to their APIs. It currently supports servers using a legacy protocol implemented by the likes of Jenkins, and it supports GitHub Actions workflows. The most requested server that’s not currently supported is GitLab. So, that’s our feature: we’ll implement support for GitLab in CCMenu.

The API wrapper

GitHub provides the GitHub Actions API, which is stable and well documented. GitLab has the GitLab API, which is also well documented. Given the nature of the problem space, they are semantically quite similar. They’re not the same, though, and we’ll see how that affects the task later.

Internally, CCMenu has three GitHub-specific files to retrieve the build status from the API: a feed reader, a response parser, and a file that contains Swift functions that wrap the GitHub API, including functions like the following:

func requestForAllPublicRepositories(user: String, token: String?) -> URLRequest

func requestForAllPrivateRepositories(token: String) -> URLRequest

func requestForWorkflows(owner: String, repository: String, token: String?) -> URLRequest

The functions return URLRequest objects, which are part of the Swift SDK and are used to make the actual network request. Because these functions are structurally quite similar they delegate the construction of the URLRequest object to one shared, internal function:

func makeRequest(method: String = "GET", baseUrl: URL, path: String,

params: Dictionary<String, String> = [:], token: String? = nil) -> URLRequest

Don’t worry if you’re not familiar with Swift, as long as you recognise the arguments and their types you’re fine.

Optional tokens

Next, we should look at the token argument in a little more detail. Requests to the API’s can be authenticated. They don’t have to be authenticated but they can be authenticated. This allows applications like CCMenu to access information that’s restricted to certain users. For most API’s, GitHub and GitLab included, the token is simply a long string that needs to be passed in an HTTP header.

In its implementation CCMenu uses an optional string for the token, which in Swift is denoted by a question mark following the type, String? in this case. This is idiomatic use, and Swift forces recipients of such optional values to deal with the optionality in a safe way, avoiding the classic null pointer problems. There are also special language features to make this easier.

Some functions are nonsensical in an unauthenticated context, like requestForAllPrivateRepositories. These declare the token as non-optional, signalling to the caller that a token must be provided.

Let’s go

I’ve tried this experiment a couple of times, during the summer using Windsurf and Sonnet 3.5, and now, recently, with Claude Code and Sonnet 4.5. The approach remained similar: break down the task into smaller chunks. For each of the chunks I asked Windsurf to come up with a plan first before asking for an implementation. With Claude Code I went straight for the implementation, relying on its internal planning; and on Git when something ended up going in the wrong direction.

As a first step I asked the agent, more or less verbatim: “Based on the GitHub files for API, feed reader, and response parser, implement the same functionality for GitLab. Only write the equivalent for these three files. Do not make changes to the UI.”

This sounded like a reasonable request, and by and large it was. Even Windsurf, with the less capable model, picked up on key differences and handled them, e.g. it recognised that what GitHub calls a repository is a project in GitLab; it saw the difference in the JSON response, where GitLab returns the array of runs at the top level while GitHub has this array as a property in a top-level object.

I hadn’t looked at the GitLab API docs myself at this stage and just from a cursory scan of the generated code everything looked pretty okay, the code compiled and even the complex function types were generated correctly, or were they?

First surprise

In the next step, I asked the agent to implement the UI to add new pipelines/workflows. I deliberately asked it not to worry about authentication yet, to just implement the flow for publicly accessible information. The discussion of that step is maybe for another memo, but the new code somehow needs to acknowledge that a token might be present in the future

var apiToken: String? = nil

and then it can use the variable in the call the wrapper function

let req = GitLabAPI.requestForGroupProjects(group: name, token: apiToken)

var projects = await fetchProjects(request: req)

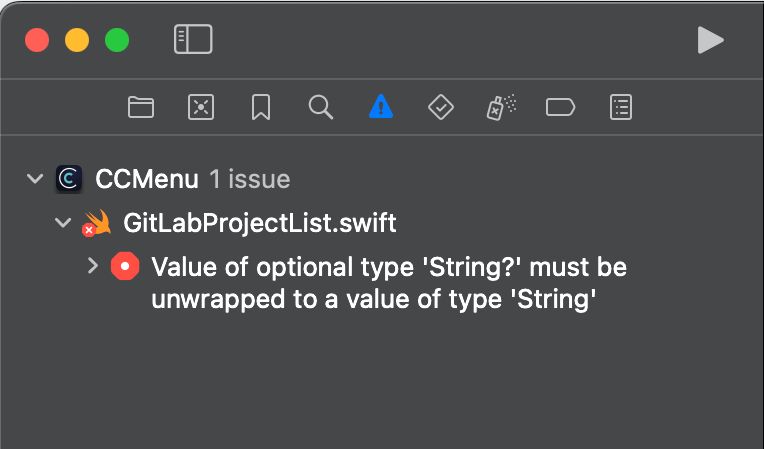

The apiToken variable is correctly declared as an optional String, initialised to nil for now. Later, some code could retrieve the token from another place depending on whether the user has decided to sign in. This code led to the first compiler error:

What’s going on here? Well, it turns out that the code for the API wrapper in the first step had a bit of a subtle problem: it declared the tokens as non-optional in all the wrapper functions, e.g.

func requestForGroupProjects(group: String, token: String) -> URLRequest

The underlying makeRequest function, for one reason or another, was created correctly, with the token declared as optional.

The code compiled because in the way the functions were written, the wrapper functions definitely have a string and that can of course be passed to a function that takes an optional string, an argument that may be a string or nothing (nil). But now, in the code above, we have an optional string and that can’t be passed to a function that needs a (definite) string.

The vibe fix

Being lazy I simply copy-pasted the error message back to Windsurf. (Building a Swift app in anything but Xcode is a whole different story, and I remember an experiment with Cline where it alternated between adding and removing explicit imports, at about 20¢ per iteration.) The fix proposed by the AI for this problem worked: it changed the call-site and inserted an empty string as a default value for when no token was present, using Swift’s ?? operator.

let req = GitLabAPI.requestForGroupProjects(group: name, token: apiToken ?? "")

var projects = await fetchProjects(request: req)

This compiles, and it kinda works: if there’s no token an empty string is substituted, which means that the argument passed to the function is either the token or the empty string, it’s always a string and never nil.

So, what’s wrong? The whole point of declaring the token as optional was to signal that the token is optional. The AI ignored this and introduced new semantics: an empty string now signals that no token is available. This is

- not idiomatic,

- not self-documenting,

- unsupported by Swift’s type system.

It also required changes in every place where this function is called.

The real fix

Of course, what the agent should’ve done is to simply change the function declaration of the wrapper function to make the token optional. With that change everything works as expected, the semantics remain intact, and the change is limited to adding a single ? to the function argument’s type, rather than spraying ?? "" all over the code.

Does it really matter?

You might ask whether I’m splitting hair here. I don’t think I am. I think this is a clear example where an AI agent left to their own would have changed the codebase for the worse, and it took a developer with experience to notice the issue and to direct the agent to the correct implementation.

Also, this is just one of many examples I encountered. At some point the agent wanted to introduce a completely unnecessary cache, and, of course, couldn’t explain why it had even suggested the cache.

It also failed to realise that the user/org overlap in GitHub doesn’t exist in the GitLab, and went to implement some complicated logic to handle a non-existing problem. It took more than nudging the agent towards the correct places in the documentation to talk it down from insisting that the logic was needed.

It also “forgot” to use existing functions to construct URLs, replicating such logic in multiple places, often without implementing all functionality, e.g. the option to overwrite the base URL for testing purposes using the defaults system on macOS.

So, in those cases, and there were more, the generated code worked. It implemented the functionality required. But the new code also would’ve added completely unnecessary complexity and it missed non-obvious functionality, decreasing the quality of the codebase and introducing subtle issues.

If working on large software systems has taught me one thing it’s that investing in the internal quality of the software, the quality of the codebase, is a worthwhile investment. Don’t get overwhelmed by technical debt. Humans and agents find it more difficult to work with a complicated codebase. Without careful oversight, though, the AI agents seem to have a strong tendency to introduce technical debt, making future development harder, for humans and agents.

One more thing

If possible, CCMenu shows the avatar of the person/actor that triggered the build. In GitHub the avatar URL is part of the response to the build status API call. GitLab has a “cleaner”, more RESTful design and keeps additional user information out of the build response. The avatar URL must be retrieved with a separate API call to a /user endpoint.

Both Windsurf and Claude Code stumbled over this in a major way. I remember a longish conversation where Claude Code wanted to convince me that the URL was in the response. (It probably got mixed up because multiple endpoints were described on the same page of the documentation.) In the end I found it easier to implement that functionality without agent support.

My conclusions

During the experiments in the summer I was on the fence. The Windsurf / Sonnet 3.5 combo did speed up writing code, but it required careful planning with prompts, and I had to switch back and forth between Windsurf and Xcode (for building, running tests, and debugging), which always felt somewhat disorientating and got tiring quickly. The quality of the generated code had significant issues, and the agent had a tendency to get stuck trying to fix a problem. So, on the whole it felt like I wasn’t getting much out of using the agent. And I traded doing what I like, writing code, for overseeing an AI with a tendency to write sloppy code.

With Claude Code and Sonnet 4.5 the story is somewhat different. It needs less prompting, and the code has better quality. It’s by no means high quality code, but it’s better, requiring less rework and less prompting to improve quality. Also, running a conversation with Claude Code in a terminal window alongside Xcode felt more natural than switching between two IDEs. For me this has tilted the scales enough to use Claude Code regularly.

latest article (Mar 04):

previous article:

Understanding Spec-Driven-Development: Kiro, spec-kit, and Tessl

next article: