Feature Toggles (aka Feature Flags)

Feature Toggles (often also refered to as Feature Flags) are a powerful technique, allowing teams to modify system behavior without changing code. They fall into various usage categories, and it's important to take that categorization into account when implementing and managing toggles. Toggles introduce complexity. We can keep that complexity in check by using smart toggle implementation practices and appropriate tools to manage our toggle configuration, but we should also aim to constrain the number of toggles in our system.

09 October 2017

Contents

- A Toggling Tale

- Categories of toggles

- Implementation Techniques

- Toggle Configuration

- Working with feature-flagged systems

“Feature Toggling” is a set of patterns which can help a team to deliver new functionality to users rapidly but safely. In this article on Feature Toggling we'll start off with a short story showing some typical scenarios where Feature Toggles are helpful. Then we'll dig into the details, covering specific patterns and practices which will help a team succeed with Feature Toggles.

Feature Toggles are also refered to as Feature Flags, Feature Bits, or Feature Flippers. These are all synonyms for the same set of techniques. Throughout this article I'll use feature toggles and feature flags interchangebly.

A Toggling Tale

Picture the scene. You're on one of several teams working on a sophisticated town planning simulation game. Your team is responsible for the core simulation engine. You have been tasked with increasing the efficiency of the Spline Reticulation algorithm. You know this will require a fairly large overhaul of the implementation which will take several weeks. Meanwhile other members of your team will need to continue some ongoing work on related areas of the codebase.

You want to avoid branching for this work if at all possible, based on previous painful experiences of merging long-lived branches in the past. Instead, you decide that the entire team will continue to work on trunk, but the developers working on the Spline Reticulation improvements will use a Feature Toggle to prevent their work from impacting the rest of the team or destabilizing the codebase.

The birth of a Feature Flag

Here's the first change introduced by the pair working on the algorithm:

before

function reticulateSplines(){

// current implementation lives here

}

these examples all use JavaScript ES2015

after

function reticulateSplines(){

var useNewAlgorithm = false;

// useNewAlgorithm = true; // UNCOMMENT IF YOU ARE WORKING ON THE NEW SR ALGORITHM

if( useNewAlgorithm ){

return enhancedSplineReticulation();

}else{

return oldFashionedSplineReticulation();

}

}

function oldFashionedSplineReticulation(){

// current implementation lives here

}

function enhancedSplineReticulation(){

// TODO: implement better SR algorithm

}

The pair have moved the current algorithm implementation into an

oldFashionedSplineReticulation function, and turned

reticulateSplines into a Toggle Point. Now if someone is

working on the new algorithm they can enable the “use new Algorithm”

Feature by uncommenting the useNewAlgorithm = true

line.

Making a flag dynamic

A few hours pass and the pair are ready to run their new algorithm through some

of the simulation engine's integration tests. They also want to exercise the old

algorithm in the same integration test run. They'll need to be able to enable or

disable the Feature dynamically, which means it's time to move on from the clunky

mechanism of commenting or uncommenting that useNewAlgorithm = true

line:

function reticulateSplines(){

if( featureIsEnabled("use-new-SR-algorithm") ){

return enhancedSplineReticulation();

}else{

return oldFashionedSplineReticulation();

}

}

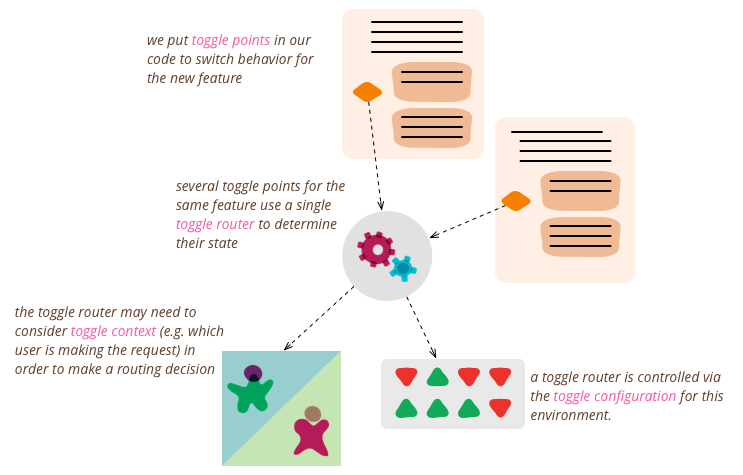

We've now introduced a featureIsEnabled function, a Toggle

Router which can be used to dynamically control which codepath is live.

There are many ways to implement a Toggle Router, varying from a simple in-memory

store to a highly sophisticated distributed system with a fancy UI. For now we'll

start with a very simple system:

function createToggleRouter(featureConfig){

return {

setFeature(featureName,isEnabled){

featureConfig[featureName] = isEnabled;

},

featureIsEnabled(featureName){

return featureConfig[featureName];

}

};

}

note that we're using ES2015's method shorthand

We can create a new toggle router based on some default configuration - perhaps read in from a config file - but we can also dynamically toggle a feature on or off. This allows automated tests to verify both sides of a toggled feature:

describe( 'spline reticulation', function(){

let toggleRouter;

let simulationEngine;

beforeEach(function(){

toggleRouter = createToggleRouter();

simulationEngine = createSimulationEngine({toggleRouter:toggleRouter});

});

it('works correctly with old algorithm', function(){

// Given

toggleRouter.setFeature("use-new-SR-algorithm",false);

// When

const result = simulationEngine.doSomethingWhichInvolvesSplineReticulation();

// Then

verifySplineReticulation(result);

});

it('works correctly with new algorithm', function(){

// Given

toggleRouter.setFeature("use-new-SR-algorithm",true);

// When

const result = simulationEngine.doSomethingWhichInvolvesSplineReticulation();

// Then

verifySplineReticulation(result);

});

});

Getting ready to release

More time passes and the team believe their new algorithm is feature-complete. To confirm this they have been modifying their higher-level automated tests so that they exercise the system both with the feature off and with it on. The team also wants to do some manual exploratory testing to ensure everything works as expected - Spline Reticulation is a critical part of the system's behavior, after all.

To perform manual testing of a feature which hasn't yet been verified as ready for general use we need to be able to have the feature Off for our general user base in production but be able to turn it On for internal users. There are a lot of different approaches to achieve this goal:

- Have the Toggle Router make decisions based on a Toggle Configuration, and make that configuration environment-specific. Only turn the new feature on in a pre-production environment.

- Allow Toggle Configuration to be modified at runtime via some form of admin UI. Use that admin UI to turn the new feature on a test environment.

- Teach the Toggle Router how to make dynamic, per-request toggling decisions. These decisions take Toggle Context into account, for example by looking for a special cookie or HTTP header. Usually Toggle Context is used as a proxy for identifying the user making the request.

(We'll be digging into these approaches in more detail later on, so don't worry if some of these concepts are new to you.)

The team decides to go with a per-request Toggle Router since it gives them a lot of flexibility. The team particularly appreciate that this will allow them to test their new algorithm without needing a separate testing environment. Instead they can simply turn the algorithm on in their production environment but only for internal users (as detected via a special cookie). The team can now turn that cookie on for themselves and verify that the new feature performs as expected.

Canary releasing

The new Spline Reticulation algorithm is looking good based on the exploratory testing done so far. However since it's such a critical part of the game's simulation engine there remains some reluctance to turn this feature on for all users. The team decide to use their Feature Flag infrastructure to perform a Canary Release, only turning the new feature on for a small percentage of their total userbase - a “canary” cohort.

The team enhance the Toggle Router by teaching it the concept of user cohorts - groups of users who consistently experience a feature as always being On or Off. A cohort of canary users is created via a random sampling of 1% of the user base - perhaps using a modulo of user ID. This canary cohort will consistently have the feature turned on, while the other 99% of the user base remain using the old algorithm. Key business metrics (user engagement, total revenue earned, etc) are monitored for both groups to gain confidence that the new algorithm does not negatively impact user behavior. Once the team are confident that the new feature has no ill effects they modify their Toggle Configuration to turn it on for the entire user base.

A/B testing

The team's product manager learns about this approach and is quite excited. She suggests that the team use a similar mechanism to perform some A/B testing. There's been a long-running debate as to whether modifying the crime rate algorithm to take pollution levels into account would increase or decrease the game's playability. They now have the ability to settle the debate using data. They plan to roll out a cheap implementation which captures the essence of the idea, controlled with a Feature Flag. They will turn the feature on for a reasonably large cohort of users, then study how those users behave compared to a “control” cohort. This approach will allow the team to resolve contentious product debates based on data, rather than HiPPOs.

This brief scenario is intended to illustrate both the basic concept of Feature Toggling but also to highlight how many different applications this core capability can have. Now that we've seen some examples of those applications let's dig a little deeper. We'll explore different categories of toggles and see what makes them different. We'll cover how to write maintainable toggle code, and finally share practices to avoid some of pitfalls of a feature-toggled system.

Categories of toggles

We've seen the fundamental facility provided by Feature Toggles - being able to ship alternative codepaths within one deployable unit and choose between them at runtime. The scenarios above also show that this facility can be used in various ways in various contexts. It can be tempting to lump all feature toggles into the same bucket, but this is a dangerous path. The design forces at play for different categories of toggles are quite different and managing them all in the same way can lead to pain down the road.

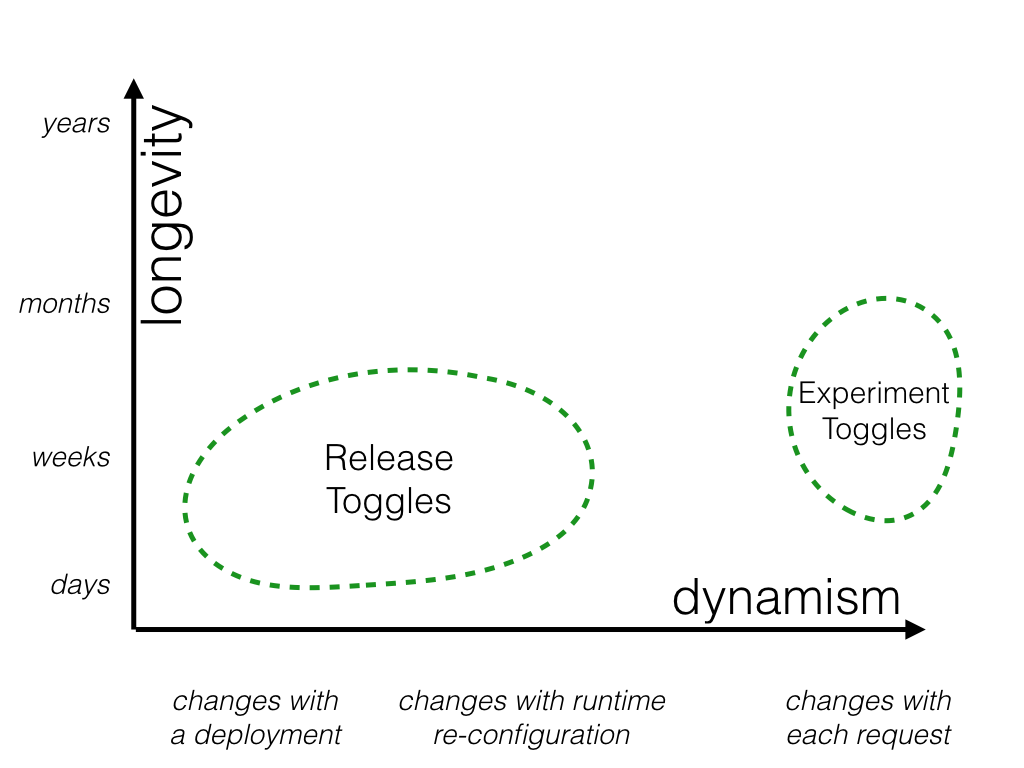

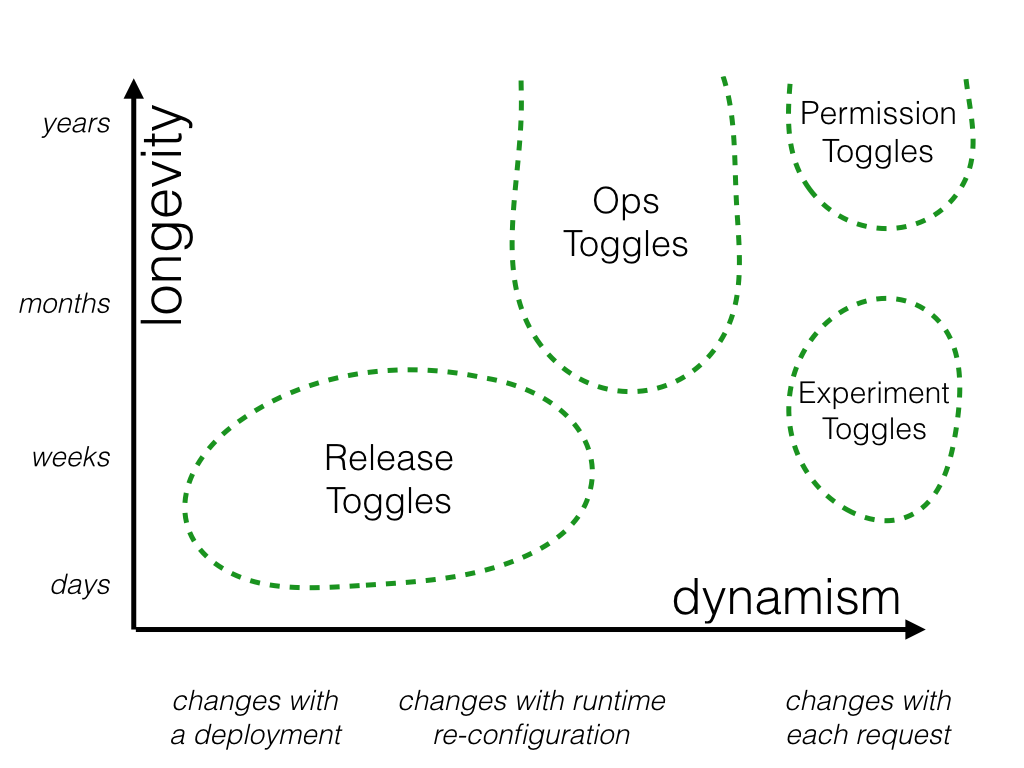

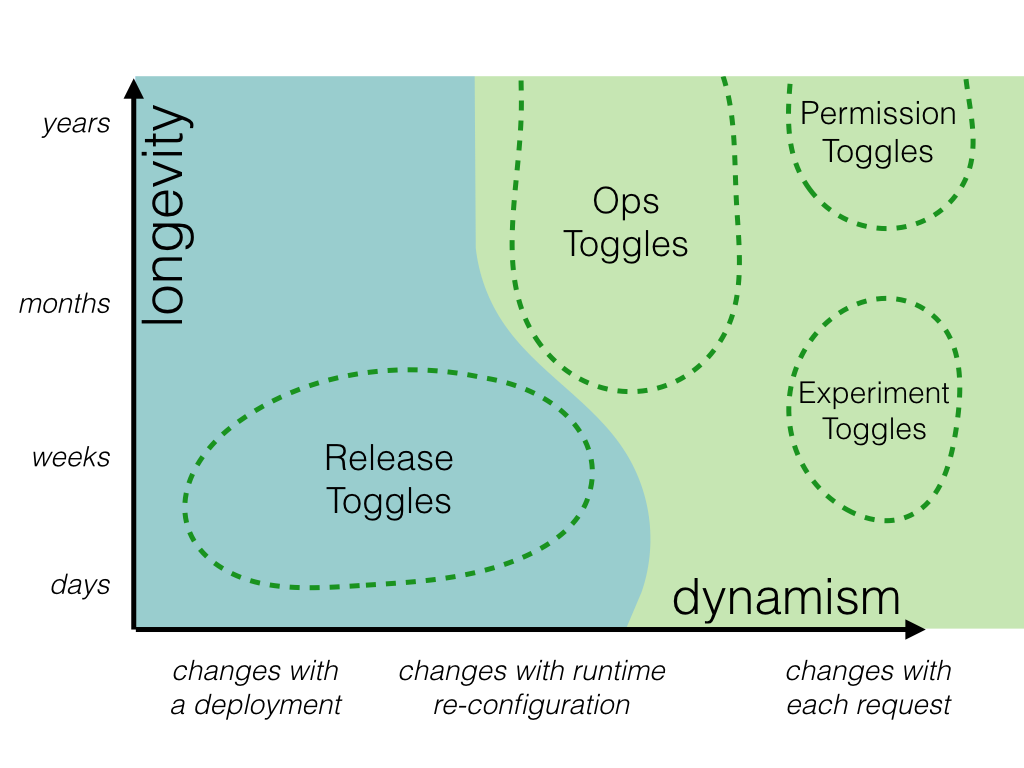

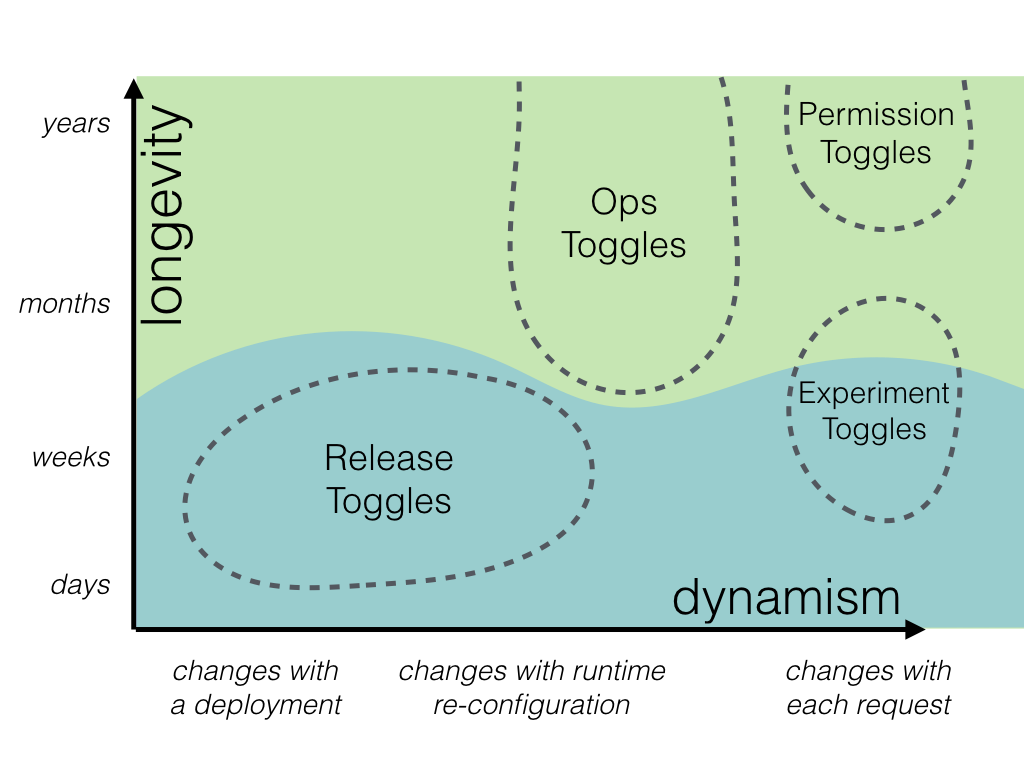

Feature toggles can be categorized across two major dimensions: how long the feature toggle will live and how dynamic the toggling decision must be. There are other factors to consider - who will manage the feature toggle, for example - but I consider longevity and dynamism to be two big factors which can help guide how to manage toggles.

Let's consider various categories of toggle through the lens of these two dimensions and see where they fit.

Release Toggles

Release Toggles allow incomplete and un-tested codepaths to be shipped to production as latent code which may never be turned on.

These are feature flags used to enable trunk-based development for teams practicing Continuous Delivery. They allow in-progress features to be checked into a shared integration branch (e.g. master or trunk) while still allowing that branch to be deployed to production at any time. Release Toggles allow incomplete and un-tested codepaths to be shipped to production as latent code which may never be turned on.

Product Managers may also use a product-centric version of this same approach to prevent half-complete product features from being exposed to their end users. For example, the product manager of an ecommerce site might not want to let users see a new Estimated Shipping Date feature which only works for one of the site's shipping partners, preferring to wait until that feature has been implemented for all shipping partners. Product Managers may have other reasons for not wanting to expose features even if they are fully implemented and tested. Feature release might be being coordinated with a marketing campaign, for example. Using Release Toggles in this way is the most common way to implement the Continuous Delivery principle of “separating [feature] release from [code] deployment.”

Release Toggles are transitionary by nature. They should generally not stick around much longer than a week or two, although product-centric toggles may need to remain in place for a longer period. The toggling decision for a Release Toggle is typically very static. Every toggling decision for a given release version will be the same, and changing that toggling decision by rolling out a new release with a toggle configuration change is usually perfectly acceptable.

Experiment Toggles

Experiment Toggles are used to perform multivariate or A/B testing. Each user of the system is placed into a cohort and at runtime the Toggle Router will consistently send a given user down one codepath or the other, based upon which cohort they are in. By tracking the aggregate behavior of different cohorts we can compare the effect of different codepaths. This technique is commonly used to make data-driven optimizations to things such as the purchase flow of an ecommerce system, or the Call To Action wording on a button.

An Experiment Toggle needs to remain in place with the same configuration long enough to generate statistically significant results. Depending on traffic patterns that might mean a lifetime of hours or weeks. Longer is unlikely to be useful, as other changes to the system risk invalidating the results of the experiment. By their nature Experiment Toggles are highly dynamic - each incoming request is likely on behalf of a different user and thus might be routed differently than the last.

Ops Toggles

These flags are used to control operational aspects of our system's behavior. We might introduce an Ops Toggle when rolling out a new feature which has unclear performance implications so that system operators can disable or degrade that feature quickly in production if needed.

Most Ops Toggles will be relatively short-lived - once confidence is gained in the operational aspects of a new feature the flag should be retired. However it's not uncommon for systems to have a small number of long-lived “Kill Switches” which allow operators of production environments to gracefully degrade non-vital system functionality when the system is enduring unusually high load. For example, when we're under heavy load we might want to disable a Recommendations panel on our home page which is relatively expensive to generate. I consulted with an online retailer that maintained Ops Toggles which could intentionally disable many non-critical features in their website's main purchasing flow just prior to a high-demand product launch. These types of long-lived Ops Toggles could be seen as a manually-managed Circuit Breaker.

As already mentioned, many of these flags are only in place for a short while, but a few key controls may be left in place for operators almost indefinitely. Since the purpose of these flags is to allow operators to quickly react to production issues they need to be re-configured extremely quickly - needing to roll out a new release in order to flip an Ops Toggle is unlikely to make an Operations person happy.

Permissioning Toggles

turning on new features for a set of internal users [is a] Champagne Brunch - an early opportunity to drink your own champagne

These flags are used to change the features or product experience that certain users receive. For example we may have a set of “premium” features which we only toggle on for our paying customers. Or perhaps we have a set of “alpha” features which are only available to internal users and another set of “beta” features which are only available to internal users plus beta users. I refer to this technique of turning on new features for a set of internal or beta users as a Champagne Brunch - an early opportunity to “drink your own champagne“.

A Champagne Brunch is similar in many ways to a Canary Release. The distinction between the two is that a Canary Released feature is exposed to a randomly selected cohort of users while a Champagne Brunch feature is exposed to a specific set of users.

When used as a way to manage a feature which is only exposed to premium users a Permissioning Toggle may be very-long lived compared to other categories of Feature Toggles - at the scale of multiple years. Since permissions are user-specific the toggling decision for a Permissioning Toggle will always be per-request, making this a very dynamic toggle.

Managing different categories of toggles

Now that we have a toggle categorization scheme we can discuss how those two dimensions of dynamism and longevity affect how we work with feature flags of different categories.

static vs dynamic toggles

Toggles which are making runtime routing decisions necessarily need more sophisticated Toggle Routers, along with more complex configuration for those routers.

For simple static routing decisions a toggle configuration can be a simple On or Off for each feature with a toggle router which is just responsible for relaying that static on/off state to the Toggle Point. As we discussed earlier, other categories of toggle are more dynamic and demand more sophisticated toggle routers. For example the router for an Experiment Toggle makes routing decisions dynamically for a given user, perhaps using some sort of consistent cohorting algorithm based on that user's id. Rather than reading a static toggle state from configuration this toggle router will instead need to read some sort of cohort configuration defining things like how large the experimental cohort and control cohort should be. That configuration would be used as an input into the cohorting algorithm.

We'll dig into more detail on different ways to manage this toggle configuration later on.

Long-lived toggles vs transient toggles

We can also divide our toggle categories into those which are essentially transient in nature vs. those which are long-lived and may be in place for years. This distinction should have a strong influence on our approach to implementing a feature's Toggle Points. If we're adding a Release Toggle which will be removed in a few days time then we can probably get away with a Toggle Point which does a simple if/else check on a Toggle Router. This is what we did with our spline reticulation example earlier:

function reticulateSplines(){

if( featureIsEnabled("use-new-SR-algorithm") ){

return enhancedSplineReticulation();

}else{

return oldFashionedSplineReticulation();

}

}

However if we're creating a new Permissioning Toggle with Toggle Points which we expect to stick around for a very long time then we certainly don't want to implement those Toggle Points by sprinkling if/else checks around indiscriminately. We'll need to use more maintainable implementation techniques.

Implementation Techniques

Feature Flags seem to beget rather messy Toggle Point code, and these Toggle Points also have a tendency to proliferate throughout a codebase. It's important to keep this tendency in check for any feature flags in your codebase, and critically important if the flag will be long-lived. There are a few implementation patterns and practices which help to reduce this issue.

De-coupling decision points from decision logic

One common mistake with Feature Toggles is to couple the place where a toggling decision is made (the Toggle Point) with the logic behind the decision (the Toggle Router). Let's look at an example. We're working on the next generation of our ecommerce system. One of our new features will allow a user to easily cancel an order by clicking a link inside their order confirmation email (aka invoice email). We're using feature flags to manage the rollout of all our next gen functionality. Our initial feature flagging implementation looks like this:

invoiceEmailer.js

const features = fetchFeatureTogglesFromSomewhere();

function generateInvoiceEmail(){

const baseEmail = buildEmailForInvoice(this.invoice);

if( features.isEnabled("next-gen-ecomm") ){

return addOrderCancellationContentToEmail(baseEmail);

}else{

return baseEmail;

}

}

While generating the invoice email our

InvoiceEmailler checks to see whether the next-gen-ecomm feature is enabled. If

it is then the emailer adds some extra order cancellation content to the

email.

While this looks like a reasonable approach, it's very brittle. The decision on

whether to include order cancellation functionality in our invoice emails is wired

directly to that rather broad next-gen-ecomm feature - using a magic string, no less. Why should

the invoice emailling code need to know that the order cancellation content is

part of the next-gen feature set? What happens if we'd like to turn on some parts

of the next-gen functionality without exposing order cancellation? Or vice versa?

What if we decide we'd like to only roll out order cancellation to certain users?

It is quite common for these sort of “toggle scope” changes to occur as features

are developed. Also bear in mind that these toggle points tend to proliferate

throughout a codebase. With our current approach since the toggling decision logic

is part of the toggle point any change to that decision logic will require

trawling through all those toggle points which have spread through the

codebase.

Happily, any problem in software can be solved by adding a layer of indirection. We can decouple a toggling decision point from the logic behind that decision like so:

featureDecisions.js

function createFeatureDecisions(features){

return {

includeOrderCancellationInEmail(){

return features.isEnabled("next-gen-ecomm");

}

// ... additional decision functions also live here ...

};

}

invoiceEmailer.js

const features = fetchFeatureTogglesFromSomewhere();

const featureDecisions = createFeatureDecisions(features);

function generateInvoiceEmail(){

const baseEmail = buildEmailForInvoice(this.invoice);

if( featureDecisions.includeOrderCancellationInEmail() ){

return addOrderCancellationContentToEmail(baseEmail);

}else{

return baseEmail;

}

}

We've introduced a FeatureDecisions object, which acts as a collection point

for any feature toggle decision logic. We create a decision method on this object

for each specific toggling decision in our code - in this case “should we include

order cancellation functionality in our invoice email” is represented by the

includeOrderCancellationInEmail decision method. Right now the decision “logic”

is a trivial pass-through to check the state of the next-gen-ecomm feature, but

now as that logic evolves we have a singular place to manage it. Whenever we want

to modify the logic of that specific toggling decision we have a single place to

go. We might want to modify the scope of the decision - for example which specific

feature flag controls the decision. Alternatively we might need to modify the

reason for the decision - from being driven by a static toggle configuration to being

driven by an A/B experiment, or by an operational concern such as an outage in

some of our order cancellation infrastructure. In all cases our invoice emailer

can remain blissfully unaware of how or why that toggling decision is being

made.

Inversion of Decision

In the previous example our invoice emailer was responsible for asking the feature flagging infrastructure how it should perform. This means our invoice emailer has one extra concept it needs to be aware of - feature flagging - and an extra module it is coupled to. This makes the invoice emailer harder to work with and think about in isolation, including making it harder to test. As feature flagging has a tendency to become more and more prevalent in a system over time we will see more and more modules becoming coupled to the feature flagging system as a global dependency. Not the ideal scenario.

In software design we can often solve these coupling issues by applying Inversion of Control. This is true in this case. Here's how we might decouple our invoice emailer from our feature flagging infrastructure:

invoiceEmailer.js

function createInvoiceEmailler(config){

return {

generateInvoiceEmail(){

const baseEmail = buildEmailForInvoice(this.invoice);

if( config.includeOrderCancellationInEmail ){

return addOrderCancellationContentToEmail(email);

}else{

return baseEmail;

}

},

// ... other invoice emailer methods ...

};

}

featureAwareFactory.js

function createFeatureAwareFactoryBasedOn(featureDecisions){

return {

invoiceEmailler(){

return createInvoiceEmailler({

includeOrderCancellationInEmail: featureDecisions.includeOrderCancellationInEmail()

});

},

// ... other factory methods ...

};

}

Now, rather than our InvoiceEmailler reaching out to FeatureDecisions it

has those decisions injected into it at construction time via a config object.

InvoiceEmailler now has no knowledge whatsoever about feature flagging. It just

knows that some aspects of its behavior can be configured at runtime. This also

makes testing InvoiceEmailler's behavior easier - we can test the way that it

generates emails both with and without order cancellation content just by passing

a different configuration option during test:

describe( 'invoice emailling', function(){

it( 'includes order cancellation content when configured to do so', function(){

// Given

const emailler = createInvoiceEmailler({includeOrderCancellationInEmail:true});

// When

const email = emailler.generateInvoiceEmail();

// Then

verifyEmailContainsOrderCancellationContent(email);

};

it( 'does not includes order cancellation content when configured to not do so', function(){

// Given

const emailler = createInvoiceEmailler({includeOrderCancellationInEmail:false});

// When

const email = emailler.generateInvoiceEmail();

// Then

verifyEmailDoesNotContainOrderCancellationContent(email);

};

});

We also introduced a FeatureAwareFactory to centralize the creation of these

decision-injected objects. This is an application of the general Dependency

Injection pattern. If a DI system were in play in our codebase then we'd probably

use that system to implement this approach.

Avoiding conditionals

In our examples so far our Toggle Point has been implemented using an if statement. This might make sense for a simple, short-lived toggle. However point conditionals are not advised anywhere where a feature will require several Toggle Points, or where you expect the Toggle Point to be long-lived. A more maintainable alternative is to implement alternative codepaths using some sort of Strategy pattern:

invoiceEmailler.js

function createInvoiceEmailler(additionalContentEnhancer){

return {

generateInvoiceEmail(){

const baseEmail = buildEmailForInvoice(this.invoice);

return additionalContentEnhancer(baseEmail);

},

// ... other invoice emailer methods ...

};

}

featureAwareFactory.js

function identityFn(x){ return x; }

function createFeatureAwareFactoryBasedOn(featureDecisions){

return {

invoiceEmailler(){

if( featureDecisions.includeOrderCancellationInEmail() ){

return createInvoiceEmailler(addOrderCancellationContentToEmail);

}else{

return createInvoiceEmailler(identityFn);

}

},

// ... other factory methods ...

};

}

Here we're applying a Strategy pattern by allowing our invoice emailer to be

configured with a content enhancement function. FeatureAwareFactory selects a

strategy when creating the invoice emailer, guided by its FeatureDecision. If

order cancellation should be in the email it passes in an enhancer function which

adds that content to the email. Otherwise it passes in an identityFn enhancer -

one which has no effect and simply passes the email back without

modifications.

Toggle Configuration

Dynamic routing vs dynamic configuration

Earlier we divided feature flags into those whose toggle routing decisions are essentially static for a given code deployment vs those whose decisions vary dynamically at runtime. It's important to note that there are two ways in which a flag's decisions might change at runtime. Firstly, something like a Ops Toggle might be dynamically re-configured from On to Off in response to a system outage. Secondly, some categories of toggles such as Permissioning Toggles and Experiment Toggles make a dynamic routing decision for each request based on some request context such as which user is making the request. The former is dynamic via re-configuration, while the later is inherently dynamic. These inherently dynamic toggles may make highly dynamic decisions but still have a configuration which is quite static, perhaps only changeable via re-deployment. Experiment Toggles are an example of this type of feature flag - we don't really need to be able to modify the parameters of an experiment at runtime. In fact doing so would likely make the experiment statistically invalid.

Prefer static configuration

Managing toggle configuration via source control and re-deployments is preferable, if the nature of the feature flag allows it. Managing toggle configuration via source control gives us the same benefits that we get by using source control for things like infrastructure as code. It can allows toggle configuration to live alongside the codebase being toggled, which provides a really big win: toggle configuration will move through your Continuous Delivery pipeline in the exact same way as a code change or an infrastructure change would. This enables the full the benefits of CD - repeatable builds which are verified in a consistent way across environments. It also greatly reduces the testing burden of feature flags. There is less need to verify how the release will perform with both a toggle Off and On, since that state is baked into the release and won't be changed (for less dynamic flags at least). Another benefit of toggle configuration living side-by-side in source control is that we can easily see the state of the toggle in previous releases, and easily recreate previous releases if needed.

Approaches for managing toggle configuration

While static configuration is preferable there are cases such as Ops Toggles where a more dynamic approach is required. Let's look at some options for managing toggle configuration, ranging from approaches which are simple but less dynamic through to some approaches which are highly sophisticated but come with a lot of additional complexity.

Hardcoded Toggle Configuration

The most basic technique - perhaps so basic as to not be considered a Feature Flag - is to simply comment or uncomment blocks of code. For example:

function reticulateSplines(){

//return oldFashionedSplineReticulation();

return enhancedSplineReticulation();

}

Slightly more sophisticated than the commenting approach is the use of a

preprocessor's #ifdef feature, where available.

Because this type of hardcoding doesn't allow dynamic re-configuration of a toggle it is only suitable for feature flags where we're willing to follow a pattern of deploying code in order to re-configure the flag.

Parameterized Toggle Configuration

The build-time configuration provided by hardcoded configuration isn't flexible enough for many use cases, including a lot of testing scenarios. A simple approach which at least allows feature flags to be re-configured without re-building an app or service is to specify Toggle Configuration via command-line arguments or environment variables. This is a simple and time-honored approach to toggling which has been around since well before anyone referred to the technique as Feature Toggling or Feature Flagging. However it comes with limitations. It can become unwieldy to coordinate configuration across a large number of processes, and changes to a toggle's configuration require either a re-deploy or at the very least a process restart (and probably privileged access to servers by the person re-configuring the toggle too).

Toggle Configuration File

Another option is to read Toggle Configuration from some sort of structured file. It's quite common for this approach to Toggle Configuration to begin life as one part of a more general application configuration file.

With a Toggle Configuration file you can now re-configure a feature flag by simply changing that file rather than re-building application code itself. However, although you don't need to re-build your app to toggle a feature in most cases you'll probably still need to perform a re-deploy in order to re-configure a flag.

Toggle Configuration in App DB

Using static files to manage toggle configuration can become cumbersome once you reach a certain scale. Modifying configuration via files is relatively fiddly. Ensuring consistency across a fleet of servers becomes a challenge, making changes consistently even more so. In response to this many organizations move Toggle Configuration into some type of centralized store, often an existing application DB. This is usually accompanied by the build-out of some form of admin UI which allows system operators, testers and product managers to view and modify Features Flags and their configuration.

Distributed Toggle Configuration

Using a general purpose DB which is already part of the system architecture to store toggle configuration is very common; it's an obvious place to go once Feature Flags are introduced and start to gain traction. However nowadays there are a breed of special-purpose hierarchical key-value stores which are a better fit for managing application configuration - services like Zookeeper, etcd, or Consul. These services form a distributed cluster which provides a shared source of environmental configuration for all nodes attached to the cluster. Configuration can be modified dynamically whenever required, and all nodes in the cluster are automatically informed of the change - a very handy bonus feature. Managing Toggle Configuration using these systems means we can have Toggle Routers on each and every node in a fleet making decisions based on Toggle Configuration which is coordinated across the entire fleet.

Some of these systems (such as Consul) come with an admin UI which provides a basic way to manage Toggle Configuration. However at some point a small custom app for administering toggle config is usually created.

Overriding configuration

So far our discussion has assumed that all configuration is provided by a singular mechanism. The reality for many systems is more sophisticated, with overriding layers of configuration coming from various sources. With Toggle Configuration it's quite common to have a default configuration along with environment-specific overrides. Those overrides may come from something as simple as an additional configuration file or something sophisticated like a Zookeeper cluster. Be aware that any environment-specific overriding runs counter to the Continuous Delivery ideal of having the exact same bits and configuration flow all the way through your delivery pipeline. Often pragmatism dictates that some environment-specific overrides are used, but striving to keep both your deployable units and your configuration as environment-agnostic as possible will lead to a simpler, safer pipeline. We'll re-visit this topic shortly when we talk about testing a feature toggled system.

Per-request overrides

An alternative approach to a environment-specific configuration overrides is to allow a toggle's On/Off state to be overridden on a per-request basis by way of a special cookie, query parameter, or HTTP header. This has a few advantages over a full configuration override. If a service is load-balanced you can still be confident that the override will be applied no matter which service instance you are hitting. You can also override feature flags in a production environment without affecting other users, and you're less likely to accidentally leave an override in place. If the per-request override mechanism uses persistent cookies then someone testing your system can configure their own custom set of toggle overrides which will remain consistently applied in their browser.

The downside of this per-request approach is that it introduces a risk that curious or malicious end-users may modify feature toggle state themselves. Some organizations may be uncomfortable with the idea that some unreleased features may be publicly accessible to a sufficiently determined party. Cryptographically signing your override configuration is one option to alleviate this concern, but regardless this approach will increase the complexity - and attack surface - of your feature toggling system.

I elaborate on this technique for cookie-based overrides in this post and have also described a ruby implementation open-sourced by myself and a Thoughtworks colleague.

Working with feature-flagged systems

While feature toggling is absolutely a helpful technique it does also bring additional complexity. There are a few techniques which can help make life easier when working with a feature-flagged system.

Expose current feature toggle configuration

It's always been a helpful practice to embed build/version numbers into a deployed artifact and expose that metadata somewhere so that a dev, tester or operator can find out what specific code is running in a given environment. The same idea should be applied with feature flags. Any system using feature flags should expose some way for an operator to discover the current state of the toggle configuration. In an HTTP-oriented SOA system this is often accomplished via some sort of metadata API endpoint or endpoints. See for example Spring Boot's Actuator endpoints.

Take advantage of structured Toggle Configuration files

It's typical to store base Toggle Configuration in some sort of structured, human-readable file (often in YAML format) managed via source-control. There are some additional benefits we can derive from this file. Including a human-readable description for each toggle is surprisingly useful, particularly for toggles managed by folks other than the core delivery team. What would you prefer to see when trying to decide whether to enable an Ops toggle during a production outage event: basic-rec-algo or “Use a simplistic recommendation algorithm. This is fast and produces less load on backend systems, but is way less accurate than our standard algorithm.”? Some teams also opt to include additional metadata in their toggle configuration files such as a creation date, a primary developer contact, or even an expiration date for toggles which are intended to be short lived.

Manage different toggles differently

As discussed earlier, there are various categories of Feature Toggles with different characteristics. These differences should be embraced, and different toggles managed in different ways, even if all the various toggles might be controlled using the same technical machinery.

Let's revisit our previous example of an ecommerce site which has a Recommended Products section on the homepage. Initially we might have placed that section behind a Release Toggle while it was under development. We might then have moved it to being behind an Experiment Toggle to validate that it was helping drive revenue. Finally we might move it behind an Ops Toggle so that we can turn it off when we're under extreme load. If we've followed the earlier advice around de-coupling decision logic from Toggle Points then these differences in toggle category should have had no impact on the Toggle Point code at all.

However from a feature flag management perspective these transitions absolutely should have an impact. As part of transitioning from Release Toggle to an Experiment Toggle the way the toggle is configured will change, and likely move to a different area - perhaps into an Admin UI rather than a yaml file in source control. Product folks will likely now manage the configuration rather than developers. Likewise, the transition from Experiment Toggle to Ops Toggle will mean another change in how the toggle is configured, where that configuration lives, and who manages the configuration.

Feature Toggles introduce validation complexity

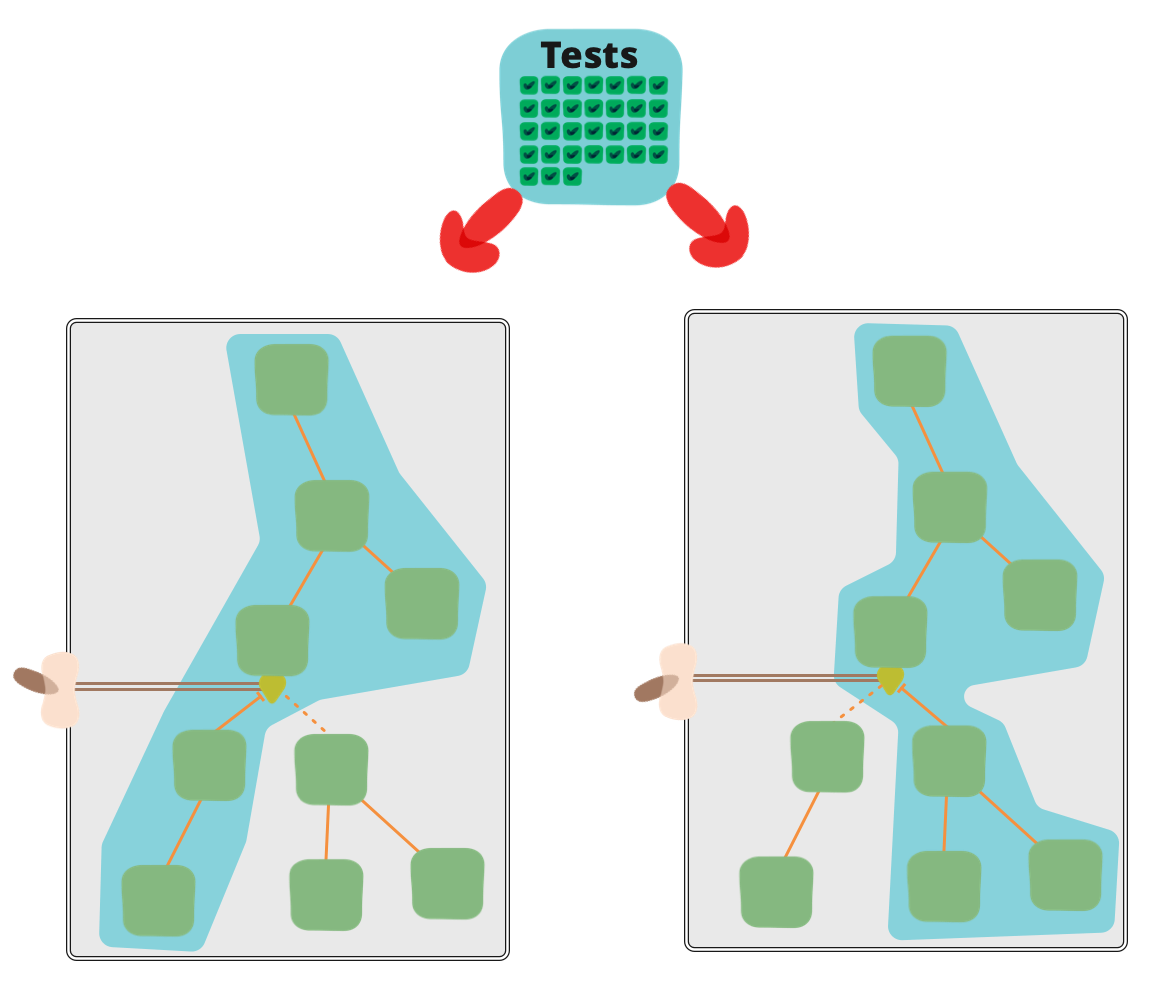

With feature-flagged systems our Continuous Delivery process becomes more complex, particularly in regard to testing. We'll often need to test multiple codepaths for the same artifact as it moves through a CD pipeline. To illustrate why, imagine we are shipping a system which can either use a new optimized tax calculation algorithm if a toggle is on, or otherwise continue to use our existing algorithm. At the time that a given deployable artifact is moving through our CD pipeline we can't know whether the toggle will at some point be turned On or Off in production - that's the whole point of feature flags after all. Therefore in order to validate all codepaths which may end up live in production we must perform test our artifact in both states: with the toggle flipped On and flipped Off.

We can see that with a single toggle in play this introduces a requirement to double up on at least some of our testing. With multiple toggles in play we have a combinatoric explosion of possible toggle states. Validating behavior for each of these states would be a monumental task. This can lead to some healthy skepticism towards Feature Flags from folks with a testing focus.

Happily, the situation isn't as bad as some testers might initially imagine. While a feature-flagged release candidate does need testing with a few toggle configurations, it is not necessary to test *every* possible combination. Most feature flags will not interact with each other, and most releases will not involve a change to the configuration of more than one feature flag.

a good convention is to enable existing or legacy behavior when a Feature Flag is Off and new or future behavior when it's On.

So, which feature toggle configurations should a team test? It's most important to test the toggle configuration which you expect to become live in production, which means the current production toggle configuration plus any toggles which you intend to release flipped On. It's also wise to test the fall-back configuration where those toggles you intend to release are also flipped Off. To avoid any surprise regressions in a future release many teams also perform some tests with all toggles flipped On. Note that this advice only makes sense if you stick to a convention of toggle semantics where existing or legacy behavior is enabled when a feature is Off and new or future behavior is enabled when a feature is On.

If your feature flag system doesn't support runtime configuration then you may have to restart the process you're testing in order to flip a toggle, or worse re-deploy an artifact into a testing environment. This can have a very detrimental effect on the cycle time of your validation process, which in turn impacts the all important feedback loop that CI/CD provides. To avoid this issue consider exposing an endpoint which allows for dynamic in-memory re-configuration of a feature flag. These types of override becomes even more necessary when you are using things like Experiment Toggles where it's even more fiddly to exercise both paths of a toggle.

This ability to dynamically re-configure specific service instances is a very sharp tool. If used inappropriately it can cause a lot of pain and confusion in a shared environment. This facility should only ever be used by automated tests, and possibly as part of manual exploratory testing and debugging. If there is a need for a more general-purpose toggle control mechanism for use in production environments it would be best built out using a real distributed configuration system as discussed in the Toggle Configuration section above.

Where to place your toggle

Toggles at the edge

For categories of toggle which need per-request context (Experiment Toggles, Permissioning Toggles) it makes sense to place Toggle Points in the edge services of your system - i.e. the publicly exposed web apps that present functionality to end users. This is where your user's individual requests first enter your domain and thus where your Toggle Router has the most context available to make toggling decisions based on the user and their request. A side-benefit of placing Toggle Points at the edge of your system is that it keeps fiddly conditional toggling logic out of the core of your system. In many cases you can place your Toggle Point right where you're rendering HTML, as in this Rails example:

someFile.erb

<%= if featureDecisions.showRecommendationsSection? %>

<%= render 'recommendations_section' %>

<% end %>

Placing Toggle Points at the edges also makes sense when you are controlling access to new user-facing features which aren't yet ready for launch. In this context you can again control access using a toggle which simply shows or hides UI elements. As an example, perhaps you are building the ability to log in to your application using Facebook but aren't ready to roll it out to users just yet. The implementation of this feature may involve changes in various parts of your architecture, but you can control exposure of the feature with a simple feature toggle at the UI layer which hides the “Log in with Facebook” button.

It's interesting to note that with some of these types of feature flag the bulk of the unreleased functionality itself might actually be publicly exposed, but sitting at a url which is not discoverable by users.

Toggles in the core

There are other types of lower-level toggle which must be placed deeper within your architecture. These toggles are usually technical in nature, and control how some functionality is implemented internally. An example would be a Release Toggle which controls whether to use a new piece of caching infrastructure in front of a third-party API or just route requests directly to that API. Localizing these toggling decisions within the service whose functionality is being toggled is the only sensible option in these cases.

Managing the carrying cost of Feature Toggles

Feature Flags have a tendency to multiply rapidly, particularly when first introduced. They are useful and cheap to create and so often a lot are created. However toggles do come with a carrying cost. They require you to introduce new abstractions or conditional logic into your code. They also introduce a significant testing burden. Knight Capital Group's $460 million dollar mistake serves as a cautionary tale on what can go wrong when you don't manage your feature flags correctly (amongst other things).

Savvy teams view their Feature Toggles as inventory which comes with a carrying cost, and work to keep that inventory as low as possible.

Savvy teams view the Feature Toggles in their codebase as inventory which comes with a carrying cost and seek to keep that inventory as low as possible. In order to keep the number of feature flags manageable a team must be proactive in removing feature flags that are no longer needed. Some teams have a rule of always adding a toggle removal task onto the team's backlog whenever a Release Toggle is first introduced. Other teams put “expiration dates” on their toggles. Some go as far as creating “time bombs” which will fail a test (or even refuse to start an application!) if a feature flag is still around after its expiration date. We can also apply a Lean approach to reducing inventory, placing a limit on the number of feature flags a system is allowed to have at any one time. Once that limit is reached if someone wants to add a new toggle they will first need to do the work to remove an existing flag.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Brandon Byars and Max Lincoln for providing detailed feedback and suggestions to early drafts of this article. Many thanks to Martin Fowler for support, advice and encouragement. Thanks to my colleagues Michael Wongwaisayawan and Leo Shaw for editorial review, and to Fernanda Alcocer for making my diagrams look less ugly.

Significant Revisions

09 October 2017: highlight feature flag as a synonym

08 February 2016: final part: complete article published

05 February 2016: part 7: working with toggled systems

02 February 2016: part 6: toggle configuration

28 January 2016: part 5: Implementation techniques

27 January 2016: part 4: managing different categories of toggles

22 January 2016: part 3: ops and permissioning toggles

21 January 2016: second installment - release and experiment toggles

19 January 2016: published first installment - A Toggling Tale