Building Infrastructure Platforms

Infrastructure Platform teams enable organisations to scale delivery by solving common product and non-functional requirements with resilient solutions. This allows other teams to focus on building their own things and releasing value for their users. But nobody said building scalable platforms was easy... In this article Poppy and Chris explore 7 key principles which can help you build the right thing right. Spoiler: don't skip strategy, user experience and research.

09 February 2022

Software has come a long way over the past 20 years. Not only has the pace of delivery increased, but the architectural complexity of systems being developed has also soared to match that pace.

Not that building software was simple in the “good” old days. If you wanted to stand up a simple web service for your business, you’d probably have to:

- Schedule in some time with an infrastructure team to find a spare [patched] rack server.

- Spend days repeatedly configuring a bunch of load balancers and domain names.

- Persuade/cajole/bribe an IT admin to let you safelist traffic through your corporate firewall.

- Figure out whatever FTP incantation would work best for your cobbled-together go-live script.

- Make a ritual sacrifice to the cruel and fickle Gods Of Prod to bless your service with good fortune.

Thankfully we’ve moved (or rather, we’re moving) away from this traditional “bare metal” IT setup to one where teams are better able to Build It & Run It. In this brave, new-ish world teams can configure their infrastructure in a similar way to how they write their services, and can in turn benefit from owning the entire system.

In this fresh and glistening new dawn of possibility, teams can build and host their products and services in whatever Unicorn configuration they choose. They can be selective with their hosting providers, technologies and monitoring strategies. They can invent a million different ways to create the same thing - And almost certainly do! However once your organisation has reached a certain size, it might no longer be efficient to have your teams building their own infrastructure. Once you start solving the same problems over and over again it might be time to start investing in a “Platform”.

An Infrastructure Platform provides common cloud components for teams to build upon and use to create their own solutions. All of the hosting infrastructure (all the networking, backups, compute etc) can be managed by the “platform team”, leaving developers free to build their solution without having to worry about it.

By building infrastructure platforms you can save time for product teams, reduce your cloud spend and increase the security and rigour of your infrastructure. For these reasons, more and more execs are finding the budget to spin up separate teams to build platform infrastructure. Unfortunately this is where things can start to go wrong. Luckily we have been through the ups and downs of building infrastructure platforms and have put together some essential steps to ensure platform success!

Have a strategy with a measurable goal

“We didn’t achieve our goal” is probably the worst thing you could hear from your stakeholders after working for weeks or months on something. In the world of infrastructure platforms this is problematic and can lead to your execs deciding to scrap the idea and spending their budget on other areas (often more product teams which can exacerbate the problem!) Preventing this isn’t rocket science - create a goal and a strategy to deliver it that all of your stakeholders are bought into.

The first step to creating a strategy is to get the right people together to define the problem. This should be a mixture of product and technical executives/budget holders aided by SMEs who can help to give context about what is happening in the organisation. Here are some examples of good problems statements:

We don’t have enough people with infrastructure capability in our top 15 product teams, and we don’t have the resources to hire the amount we need, delaying time to market for our products by an average of 6 months

We have had outages of our products totalling 160 hours and over $2 million lost revenue in the past 18 months

These problem statements are honest about the challenge and easy to understand. If you can’t put together a problem statement maybe you don’t need an infrastructure platform. And if you have many problems which you want to tackle by creating an infrastructure platform then do list these out, but choose one which is the driver and your focus. Having more than one problem statement can lead to overpromising what your infrastructure team will achieve and not deliver; prioritising too many things with different results and not really achieving any.

Now convert your problem statement into a goal. For example:

Provide the top 15 product teams with the infrastructure they can easily consume to reduce the time to market by an average of 6 months

Have less than 3 hours of outages in the next 18 months

Now you can create a strategy to tackle your problem. Here’s some fun ideas on how:

Post mortem session(s)

- If you followed the previous steps you’ve identified a problem statement which exists in your organisation, so it’s probably a good idea to find out why this is a problem. Get everyone who has context of the problem together for a post mortem session (ideally people who will have different perspectives and visibility of the problem).

- Upfront make sure everyone is committed to the session being a safe space where honesty is celebrated and blame is absent.

- The purpose of the session is to find the root cause of problems. It can be helpful to:

- Draw out a timeline of things which happened which may have contributed to the problem. Help each other to build the picture of the potential causes of the problem.

- Use the 5 whys technique but make sure you don’t focus on finding a single root cause, often problems are caused by a combination of factors together.

- Once you’ve found your root causes, ask what needs to change so that this doesn’t happen again; Do you need to create some security guidelines? Do you need to ensure all teams are using CI/CD practises and tooling? Do you need QAs on each team? This list also goes on…

Future backwards session

- Map what would need to be true to meet your goal e.g. “all products have multiple Availability Zones”, “all services must have a five-nines SLA”.

- Now figure out how to make these things true. Do you need to spin an infrastructure platform team up? Do you need to hire more people? Do you need to change some governance? Do you need to embed experts such as infosec into teams earlier in development? And the list goes on…

We highly recommend doing both of these sessions. Using both a past and future lens can lead to new insights for what you need to do to meet your goal and solve your problem. Do the post mortem first, as our brains seem to find it easier to think about the past before the future! If you only have time for one, then do a future backwards session, because the scope of this is slightly wider since the future hasn’t happened yet and can foster wider ideation and outside of the box thinking.

Hopefully by the end of doing one or both of these sessions, you have a wonderfully practical list of things you need to do to meet your goal. This is your strategy (side note that visions and goals aren’t strategies!!! See Good strategy Bad strategy by Richard P. Rumelt).

Interestingly you might decide that spinning up a team to build an infrastructure platform isn’t part of your strategy and that’s fine! Infra platforms aren’t something every organisation needs, you can skip the rest of this article and go read something far more interesting on Martin’s Blog! If you are lucky enough to be creating an infrastructure platform as part of your strategy then buckle up for some more stellar advice.

Find out what your customers need

When us Agilists hear about a product which was built but then had no users to speak of, we roll our eyes knowing that they mustn’t have done the appropriate user research. So you might find it surprising to know that many organisations build platform infrastructure, and then can’t get any teams to use them. This might be because no one needed the product in the first place. Maybe you built your infrastructure product too late and they had already built their own? Maybe you built it too early and they were too busy with their other backlog priorities to care? Maybe what you built didn’t quite meet their user needs?

So before deciding what to build, do a discovery as you would with a customer-facing product. For those who haven’t done one before, a discovery is a (usually) timeboxed activity where a team of people (ideally the team who will build a solution) try to understand the problem space/reason they are building something. At the end of this period of discovery the team should understand who the users of the infrastructure product are (there can be more than one type of user), what problems the users have, what the users are doing well, and some high level idea of what infrastructure product your team will build. You can also investigate anything else which might be useful, for example what technology people are using, what people have tried before which didn’t work, governance which you need to know about etc.

By defining our problem statement as part of our strategy work we understand the organisation needs. Now we need to understand how this overlaps with our user needs, (our users being product teams - predominantly developers). Make sure to focus your activities with your strategy in mind. For example if your strategy is security focussed, then you might:

- Highlight examples of security breaches including what caused them (use info from a post mortem if you did one)

- Interview a variety of people who are involved in security including Head of Security, Head of Technology, Tech leads, developers, QAs, Delivery managers, BAs, infosec.

- Map out the existing security lifecycle of a product using workshopping such as Event Storming. Rinse and repeat with as many teams as you can within your timeframe that you want your infrastructure platform to be serving.

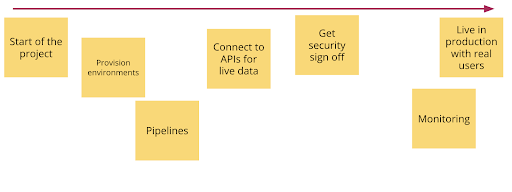

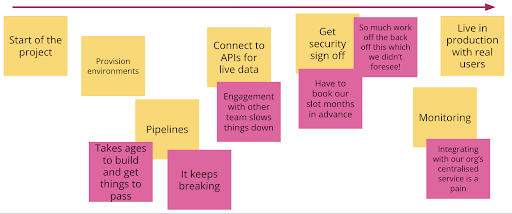

If you only do one thing as part of your discovery, do Event Storming. Get a team or a bunch of teams who will be your customers in a physical room with a physical wall or on a call with a virtual whiteboard. Draw a timeline with a start and end point on this diagram. For an infrastructure platform discovery it can be useful to map from the start of a project to being live in production with users.

Then ask everyone to map all the things from the start of a project to it being live in production in sticky notes of one colour.

Next ask the teams to overlay any pain points, things which are frustrating or things which don’t always go well in another colour.

If you have time, you can overlay any other information which might be useful to give you an idea of the problem space that your potential users are facing such as the technologies or systems used, the time it takes for different parts, different teams which might be involved in the different parts (this one is useful if you decide to deepdive into an area after the session). During the session and after the session, the facilitators (aka the team doing the discovery) should make sure they understand the context around each sticky, deep diving and doing further investigation into areas of interest where needed.

Once you’ve done some discovery activities and have got an idea of what your users need to deliver their customer-facing products, then prioritise what can deliver the most value the quickest. There are tons of online resources which can help you shape your discovery - a good one is gov.uk

Onboard users early

“That won’t work for us” is maybe the worst thing you can hear about your infrastructure platform, especially if it comes after you’ve done all the right things and truly understood the needs of your users (developers) and the needs of their end users. In fact, let's ask how you might have gotten into this position. As you break down the infrastructure product you are creating into epics and stories and really start to get into the detail, you and your team will be making decisions about the product. Some decisions you make might seem small and inconsequential so you don’t validate every little detail with your users, and naturally you don’t want to slow down or stop your build progress every time a small implementation detail has to be defined. This is fine by the way! But, if months go by and you haven’t got feedback about these small decisions you’ve made which ultimately make up your infrastructure product, then the risk that what you’re building might not quite work for your users is going to be ever increasing.

In traditional product development you would define a minimum viable product (MVP) and get early feedback. One thing we've battled with in general - but even more so with infrastructure platforms - is how to know what a “viable” product is. Thinking back to what your reason is for building an infrastructure platform, it might be that viable is when you have reduced security risk, or decreased time to market for a team however if you don’t release a product to users (developers on product teams) until it’s “viable” from this definition, then a “that won’t work for us” response becomes more and more likely. So when thinking about infrastructure platforms, we like to think about the Shortest Path to Value (SPV) as the time when we want our first users to onboard. Shortest Path to Value is as it sounds, what is the soonest you can get value, either for your team, your users, your organisation or a mixture. We like the SPV approach as it helps you continuously think about when the earliest opportunity to learn is there and push for a thinner slice. So if you haven’t noticed, the point here is to onboard users as early as possible so that you can find out what works, find out what doesn’t work and decide where you should put your next development efforts into improving this infra product for the wider consumption in your organisation.

Communicate your technical vision

Perhaps unsurprisingly the key here is to make sure you articulate your technical vision early-on. You want to prevent multiple teams from building out the same thing as you (it happens!) Make sure your stakeholders know what you are doing and why. Not only will this build confidence in your solution, but it’s another opportunity to get early insight into your product!

Your vision doesn’t have to be some high-fidelity series of UML masterpieces (though a lot of the common modelling formats there are quite useful to lean on). Grab a whiteboard and a sharpie/dry-erase marker and go nuts. When you’re trying to communicate ideas things are going to get messy, so being easily able to wipe down and start again is key! Try to avoid the temptation to immediately jump into a CAD program for these kinds of diagrams, they end up distancing you from the creative process.

That being said, there are some useful tools out there which are lightweight enough to implement at this stage. Things like:

C4 Diagrams

This was introduced by Simon Brown way back at the TURN OF THE MILLENIA. Built on UML concepts, C4 provides not only a vocabulary for defining systems, but also a method of decomposing a vision into 4 different “Levels” which you can then use to describe different ideas.

- Level 1: Context

- The Context diagram is the most “zoomed out” of the 4. Here you loosely highlight the system being described and how it relates to neighbouring systems and users. Use this to frame conversations about interactions with your platform and how your users might onboard.

- Level 2: Container

- The Container diagram explodes the overall Context into a bunch of “Containers” which may contain applications and data stores. By drilling down into some of the applications that describe your platform you can drive conversations with your team about architectural choices. You can even take your design to SRE folks to discuss any alerting or monitoring considerations.

- Level 3: Component

- Once you understand the containers that make up your platform you can take things to the next level. Select one of your Containers and explode it further. See the interactions between the modules in the container and how they relate to components in other parts of your universe. This level of abstraction is useful to describe the responsibilities of the inner workings of your system.

- Level 4: Code

- The Code diagram is the optional 4th way of describing a system. At this level you’re literally describing the interactions between classes and modules at a code level. Given the overhead of creating this kind of diagram it is often useful to use automated tools to generate them. Do make sure though that you’re not just producing Vanity Diagrams for the sake of it. These diagrams can be super useful for describing unusual or legacy design decisions.

Once you’ve been able to build your technical vision, use it to communicate your progress! Bring it along to your sprint demos. Use it to guide design conversations with your team. Take it for a little day-trip to your next threat modelling exercise. We’ve only scratched the surface of C4 Diagrams in this piece. There are loads of great articles out there which explore this in more depth - to explore start with this article on InfoQ.

And don’t stop there! Remember that although the above techniques will help guide the conversations for now; software is a living organism that may be there long after you’ve retired. Being able to communicate your technical vision as a series of decisions which were able to guide your hand is another useful tool.

Architectural Decision Records

We’ve spoken about using C4 Diagrams as a means to mapping out your architecture. By providing a series of “windows” into your architecture at different conceptual levels, C4 diagrams help to describe software to different audiences and for different purposes. So whilst C4 Diagrams are useful for mapping out your architectural present or future; ADRs are a technique that you can use for describing your architectural past.

Architectural Decision Records are a lightweight mechanism to document WHAT and HOW decisions were made to build your software. Including these in your platform repositories is akin to leaving future teams/future you a series of well-constructed clues about why the system is the way it is!

A Sample ADR

There are several good tools available to help you make your ADR documents consistent (Nat Pryce’s adr-tools is very good). But generally speaking the format for an Architectural Decision Record is as follows:

| name | description |

|---|---|

| Date | 2021-06-09 |

| Status | Pending/Accepted/Rejected |

| Context | A pithy sentence which describes the reason that a decision needs to be made. |

| Decision | The outcome of the decision being made. It’s very useful to relate the decision to the wider context. |

| Consequences | Any consequences that may result from making the decision. This may relate to the team owning the software, other components relating to the platform or even the wider organisation. |

| Who was there | Who was involved in the decision? This isn’t intended to be a wagging finger in the direction of who qualified the decision or was responsible for it. Moreover, it’s a way of adding organisational transparency to the record so as to aid future conversations. |

Ever been in a situation where you’ve identified some weirdness in your code? Ever wanted to reach back in time and ask whomever made that decision why something is the way it is? Ever been stuck trying to diagnose a production outage but for some reason you don’t have any documentation or meaningful tests? ADRs are a great way to supplement your working code with a living series of snapshots which document your system and the surrounding ecosystem. If you’re interested in reading more about ADRs you can read a little more about them in the context of Harmel-Law's Advice Process.

Put yourselves in your users’ shoes

If you have any internal tools or services in your organisation which you found super easy and pain free to onboard with, then you are lucky! From our experience it’s still so surprising when you get access to the things you want. So imagine a world where you have spent time and effort to build your infrastructure platform and teams who onboard say “wow, that was easy!”. No matter your reason for building an infrastructure platform, this should be your aim! Things don’t always go so well if you have to mandate the usage of your infra products, so you’re going to have to actually make an effort to make people want to use your product.

In regular product development, we might have people with capabilities such as user research, service design, content writing, and user experience experts. When building a platform, it’s easy to forget about filling these roles but it’s just as important if you want people in your organisation to enjoy using your platform products. So make sure that there is someone in your team driving end to end service design of your infrastructure product whether it is a developer, BA or UX person.

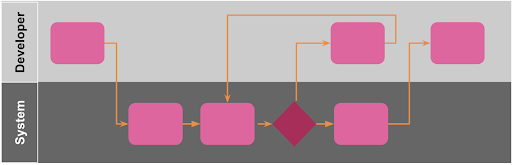

An easy way to get started is to draw out your user journey. Let’s take an example of onboarding.

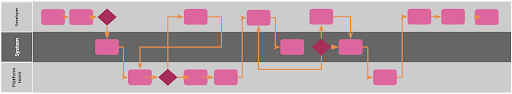

Even without context on what this journey is, there are things to look out for which might signal a not so friendly user experience:

- Handoffs between the developer user and your platform team

- There are a few loops which might set a developer user back in their onboarding

- Lack of automation - a lot is being done by the platform team

- There are 9 steps for our developer user to complete before onboarding with possible waiting time and delays in between

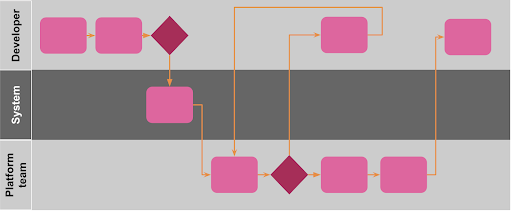

Ideally you want your onboarding process to look something like this:

As you can see, there is no Platform team involvement for the onboarding so it is fully self service, and there are only three steps for our developer user to follow. To achieve such a great experience for your users, you need to be thinking about what you can automate, and what you can simplify. There will be tradeoffs between a simple user journey and a simple codebase (as described in “don’t over-complicate things”). Both are important, so you need a strong product owner who can ensure that this tradeoff works for the reason you are delivering a platform in the first place i.e. if you are building a platform so that you can take your products to market faster, then a seamless and quick onboarding process is super important.

In reality, your onboarding process might look something more like this

Especially when you release your mvp (see previous section). Apply this thinking to any other interactions or processes which teams might have to go through when using your product. By creating a great user experience (and also having an infra product people want of course), you should not only have happy users but also great publicity within your organisation so that other teams want to onboard. Please don’t ignore this advice and get in a position where your organisation is mandating the usage of your nightmare-to-consume infrastructure platform and all your developer teams are sad :(

Don’t over-complicate things

All software is broken. Not to put too much of a downer on things, but every line of code that you write has a very high chance of becoming quickly obsolete. Every If Statement, design pattern, every line of configuration has the potential to break or to introduce a weird side effect. These may manifest themselves as a hard-to-reproduce bug or a full-blown outage. Your platform is no different! Just because your product doesn’t have a fancy, responsive UI or highly-available API doesn’t mean it isn’t liable to develop bugs. And what happens if the thing you’re building is a platform upon which other teams are building out their own services?

When you’re developing an infrastructure platform that other teams are dependent upon; your customers' dev environments are your production environments. If your platform takes a tumble you might end up taking everyone else with you. You really don’t want to risk introducing downtime into another team’s dev processes. It can erode trust and even end up hurting the relationships with the very people you were trying to help!

One of the main (and horribly insidious) reasons for bugs in software relates to complexity. The greater the number of supported features, the more that your platform is trying to do, the more that can go wrong. But what’s one of the main reasons for complexity arising in platform teams?

Conway's Law, for those that might not already be horribly, intimately acquainted, states that organizations tend to design systems which mirror their own internal communication structure. What this means from a software perspective is that often a system may be designed with certain “caveats” or “workarounds” which cater for a certain snapshot of time in an organisation’s history. Whilst this isn’t necessarily a bad thing, it can too easily influence the design decisions we make on the ground. If you’re building an API these kinds of design decisions might be easily-enough handled within the team. But if you’re building a system with a number of different integrations for many different teams (and their plethora of different nuances), this gets to be more of a problem.

So where’s the sweet spot between writing a bunch of finely-grained components which are really tightly-coupled to business processes, and building a platform which can support the growth of your organisation?

Generally speaking every component that you write as a team is another thing that’ll need to be measured, maintained and supported. Granted you may be limited by existing architectural debt, compliance constraints or security safeguards. The take away from us here is just to think twice before you introduce another component to your solution. Every moving part you develop is an investment in post-live support and another potential failure mode.

Measure the important stuff

An article about Building Better Infrastructure Platforms would not be complete without a note about measuring things. We mentioned earlier about making sure you define a strategy with a measurable goal. So what does success look like? Is this something you can extract with code? Maybe you want to increase your users’ deployment frequency by reducing their operational friction? Maybe your true north is around providing a stable and secure artifact repository that teams can depend upon? Take some time to see if you can turn this success metric into a lightweight dashboard. Being able to celebrate your Wins is a massive boon both for your team’s morale and for helping to build confidence in your platform with the wider organisation!

The Four Key Metrics

We literally couldn’t talk about metrics without mentioning this. From the 2018 book Accelerate, (A brilliant read about the dev team performance), the four key metrics are a simple enough indicator for high-performing teams. It’s indicated by:

- Delivery lead time

- Rather than the time taken between “Please and Thank you” (from initial ideation through analysis, development and delivery), here we’re talking about the time it takes from code being committed to code successfully running in production. The shorter (or perhaps more importantly the more predictable) the duration of development, the higher-performing the team can be said to be.

- Deployment frequency

- Why is the number of times a team deploys their software important? Typically speaking a high frequency of deployments is also linked to much smaller deployments. With smaller changesets being deployed into your production environment, the safer your deployments are and the easier to both test and remediate if there’s a need to roll back. If you couple a high deployment frequency with a short delivery lead time you are much more able to deliver value for your customers quickly and safely.

- Change failure rate

-

This brings us to “change failure rate”. The fewer times your deployments fail when you pull the trigger to get into Production, the higher-performing the team can be said to be. But what defines a deployment failure? A common misconception is for change failure rate to be equated to red pipelines only. Whilst this is useful as an indicator for general CI/CD health; change failure rate actually describes scenarios where Production has been impaired by a deployment, and required a rollback or fix-forward to remediate.

If you’re able to keep an eye on this as a metric, and reflect upon it during your team retrospectives and planning you might be able to surface areas of technical debt which you can focus upon.

- Mean time to recovery

- The last of the 4 key metrics speaks to the recovery time of your software in the event of a deployment failure. Given that your failed deployment may result in an outage for your users, understanding your current exposure gives you an idea of where you might need to spend some more effort. That’s all very well and good for conventional “Product” development, but what about for your platform? It turns out the 4 key metrics are even MORE important if you’re building out a common platform for folks. Your downtime is now the downtime of other software teams. You are now a critical dependency in your organisation’s ability to deliver software!

It’s important to recognise that the 4 key metrics are incredibly useful trailing indicators - They can give you a measure for how well you’ve achieved your goals. But what if you’ve not managed to get anyone to adopt your platform? Arguably the 4 key metrics only become useful once you have some users. Before you get here, focusing on understanding and promoting adoption is key!

There are many more options for measuring your software delivery, but how much is too much? Sometimes by focussing too much on measuring everything you can miss some of the more obviously-fixable things that are hiding in plain sight. Recognise that not all facets of platform design succumb to measurement. Equally, beware so-called “vanity metrics”. If you choose to measure something please do make sure that it’s relevant and actionable. If you select a metric that doesn’t turn a lever for your team or your users, you’re just making more work for yourselves. Pick the important things, throw away the rest!

Developing an infrastructure platform for other engineering teams may seem like an entirely different beast to creating more traditional software. But by adopting some or all of the 7 principles outlined in this article, we think that you'll have a much better idea of your organisation’s true needs, a way to measure your success and ultimately a way of communicating your intent.

Significant Revisions

09 February 2022: Published rest of the article

08 February 2022: Published “Communicate your technical vision” and “Put yourselves in your users’ shoes”

02 February 2022: Published “Find out what your customers need” and “Onboard users early”

01 February 2022: Published “Have a strategy with a measurable goal”