Illustrative Programming

30 June 2009

What's the most common programming language in the world?

I'm not sure how you could go about measuring this, but one thing you'd need to do is consider what we mean by programming. My candidate answer considers that the most popular programming language is one used widely by people who do not consider themselves as programmers. This language is Excel, or more generally spreadsheets.

Spreadsheets are easily used for small tasks, but are also used for surprisingly complex and important things. Often I've seen professional programmers gulp when they realize that some vital business function is being run off some spreadsheet that they'd find too complicated to muck with.

In general, we've not had much success with programming languages for these kind of LayProgrammers. Whenever someone talks about some new environment that's going to allow people to specify complex behavior “without programming” I mention COBOL, which was originally designed to get rid of programmers. So it's important to consider what Excel can teach us about programming environments.

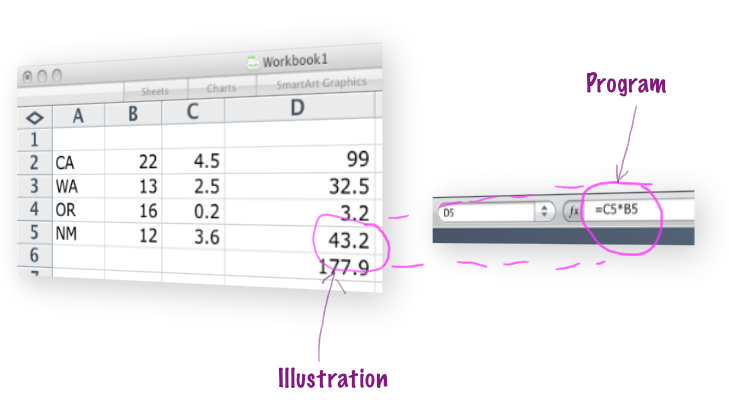

One property of spreadsheets, that I think is important, is its ability to fuse the execution of the program together with its definition. When you look at a spreadsheet, the formulae of the spreadsheet are not immediately apparent, instead what you see is the calculated numbers - an illustration of what the program does.

Using examples as a first class element of a programming environment crops up in other places - UI designers also have this. Providing a concrete illustration of the program output helps people understand what the program definition does, so they can more easily reason about behavior.

So why do I feel we need this particular Neologism? Essentially because I think it deserves more thought. We pass by illustrative programming examples without really thinking about them or what makes them special - or even that they are special in some way. We've used illustrative programming for years, but we've not paid enough attention to it. We've not thought enough about what are its essential qualities and what its strengths and weaknesses are.

I've chosen the term “Illustrative Programming” to describe this, partly because “example” is so heavily used (and illustration isn't) but also because the term “illustration” reinforces the explanatory nature of the example execution. Illustrations are meant to help explain a concept by giving you a different way of looking at it - similarly an illustrative execution is there to help you see what your program does as you change it.

When trying to make a concept explicit like this, it's useful to think about the boundary cases. One boundary is the notion of using projections of program information during editing, such as an IDE that shows you the class hierarchy while you are working on the code. In some ways this is similar, as the hierarchy display is continuously updated as you modify the program, but the crucial difference is that the hierarchy can be derived from static information about the program. Illustrative programming requires information from the actual running of the program.

I also see illustrative programming as a concept beyond the classic REPL loop of dynamic languages. REPL loops allow you to explore execution, but they don't make the examples front and center in the way that a spreadsheet does its values. Illustrative programming techniques put the illustration in the foreground of your editing experience. The program retreats to the background, peeping out only when we want to explore a part of the illustration.

I don't think that illustrative programming is all goodness. One problem I've seen with spreadsheets and with GUI designers is that they do a good job of revealing what a program does, but de-emphasizes program structure. As a result complicated spreadsheets and UI panels are often difficult to understand and modify. They are often riven with uncontrolled copy-and-paste programming.

This strikes me as a consequence of the fact that the program is de-emphasized in favor of the illustrations. As a result the programmers don't think to take care of it. We suffer enough from a lack of care of programs even in regular programming, so it's hardly shocking that this occurs with illustrative programs written by lay programmers. But this problem leads us to create programs that quickly become unmaintainable as they grow. The challenge for future illustrative programming environments is to help develop a well structured program behind the illustrations - although the illustrations may also make us rethink what a well structured program is.

The hard part of this may well be the ability to easily create new abstractions. One of my observations of rich client UI software is that they get tangled because the UI builders think only in terms of screens and controls. My experiments here suggest to me that you need to find the right abstractions for you program, which will take a different form. But these abstractions won't be supported by the screen builder as it can only illustrate the abstractions it knows about.

My colleagues Rebecca Parsons and Neal Ford have been spending a lot of time involved in thinking along these lines too. So here's some thoughts that Neal had in an email exchange

- I think these tools work best for lay people (thus, your link to LayProgrammers). However, in general, tools like this slow down experienced/power users. When you mention UI panels, the Mac is rife with these types of controls. I spend a great deal of time in Keynote, fiddling with the inspector. At least all those controls are in one place (not like the new ribbon stuff). I would much prefer a markup language I could use to directly define stuff, with macros, snippets, and all the other things I'm accustomed to as a developer.

- as these tools grow, they get unwieldy (perhaps because they are ceasing to be domain specific enough?) Look at Word, Excel, and PowerPoint. They had to invent new UI metaphors to expose all the functionality of those tools. APIs in programming languages scale much better, with several orders of magnitude more density before they become hard to navigate.

- All the best-practices and tools don't exist there: refactoring, levels of testing, etc. Also, you loose the connection to text, meaning that macro facilities either don't exist or complex one-offs. I think a good comparison that highlights the limitations of Illustrative Programming is the comparison between bash (large, arcane, powerful, quirky) to Automator. I almost never use Automator because it suffers from Dietzler's Law: it's always lacking 10% of what I need. I gladly deal with the crufty surface area of bash because of the more power afforded.

- I share your bullishness around these types of tools, but they are a long time from being useful for full-bore Agile development. I hope they mature fast.

-- Neal Ford

One of the few people to take illustrative programming seriously is Jonathan Edwards. He's come up with many very imaginative ideas as to what such an environment should look like. His vision of illustrative programming is also closely bound to the notions of projectional editing and controlled copy-and-paste.

The trigger for me in wanting to coin a term here, is the use of illustrative programming by Language Workbenches by people like IntentionalSoftware. These Language Workbenches encourage you to build illustrative DSLs. Using illustration is important in this case since this should help engage lay-programmers, which is one of the aims of using DSLs. The challenge is to do this without falling into the trap of poor program structure.