Dev Ops Culture

9 July 2015

Agile software development has broken down some of the silos between requirements analysis, testing and development. Deployment, operations and maintenance are other activities which have suffered a similar separation from the rest of the software development process. The DevOps movement is aimed at removing these silos and encouraging collaboration between development and operations.

DevOps has become possible largely due to a combination of new operations tools and established agile engineering practices 1, but these are not enough to realize the benefits of DevOps. Even with the best tools, DevOps is just another buzzword if you don't have the right culture.

1: Operations tools include virtualization, cloud computing and automated configuration management. These are often supported by engineering practices such as Continuous Integration, evolutionary design and clean code.

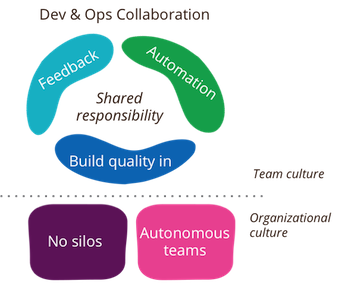

The primary characteristic of DevOps culture is increased collaboration between the roles of development and operations. There are some important cultural shifts, within teams and at an organizational level, that support this collaboration.

DevOps requires an important cultural shift, within teams and in the organization

An attitude of shared responsibility is an aspect of DevOps culture that encourages closer collaboration. It’s easy for a development team to become disinterested in the operation and maintenance of a system if it is handed over to another team to look after. If a development team shares the responsibility of looking after a system over the course of its lifetime, they are able to share the operations staff’s pain and so identify ways to simplify deployment and maintenance (e.g. by automating deployments and improving logging). They may also gain additional ObservedRequirements from monitoring the system in production. When operations staff share responsibility of a system’s business goals, they are able to work more closely with developers to better understand the operational needs of a system and help meet these. In practice, collaboration often begins with an increased awareness from developers of operational concerns (such as deployment and monitoring) and the adoption of new automation tools and practices by operations staff.

Some organizational shifts are required to support a culture of shared responsibilities. There should be no silos between development and operations. Handover periods and documentation are a poor substitute for working together on a solution from the start. It is helpful to adjust resourcing structures to allow operations staff to get involved with teams early. Having the developers and operations staff co-located will help them to work together. Handovers and sign-offs discourage people from sharing responsibility and contributes to a culture of blame. Instead, developers and operations staff should both be responsible for the successes and failures of a system. DevOps culture blurs the line between the roles of developer and operations staff and may eventually eliminate the distinction. One common anti-pattern when introducing DevOps to an organization is to assign someone the role of 'DevOps' or to call a team a 'DevOps team'. Doing so perpetuates the kinds of silos that DevOps aims to break down and prevents DevOps culture and practices from spreading and being adopted by the wider organization.

Another valuable organizational shift is to support autonomous teams. In order to collaborate effectively, developers and operations staff need to be able to make decisions and apply changes without convoluted decision making processes. This involves trusting teams, changing the way risk is managed and creating an environment that is free of a fear of failure. For example, a team that has to produce a list of changes for sign-off in order to deploy to a testing environment is likely to be delayed frequently. Instead of requiring such a manual check, it is possible to rely on version control, which is fully auditable. Changes in version control can even be linked to tickets in the team's project management tool. Without the manual sign-off, the team can automate their deployments and speed up their testing cycle.

One effect of a shift towards DevOps culture is that it becomes easier to put new code in production. This necessitates some further cultural changes. In order to ensure that changes in production are sound, the team needs to value building quality into the development process. This includes cross-functional concerns such as performance and security. The techniques of ContinuousDelivery, including SelfTestingCode, form a basis which allows regular, low-risk deployments.

It is also important for the team to value feedback, in order to continuously improve the way in which developers and operations staff work together as well as the system itself. Production monitoring is a helpful feedback loop for diagnosing issues and spotting potential improvements.

Automation is a cornerstone of the DevOps movement and facilitates collaboration. Automating tasks such as testing, configuration and deployment frees people up to focus on other valuable activities and reduces the chance of human error. A helpful side effect of automation is that automated scripts and tests serve as useful, always up-to-date documentation of the system. Automating server configuration, for example, removes the guesswork associated with a SnowflakeServer and means that developers and operations staff are equally able to know and change how a server is configured.

Notes

1: Operations tools include virtualization, cloud computing and automated configuration management. These are often supported by engineering practices such as Continuous Integration, evolutionary design and clean code.